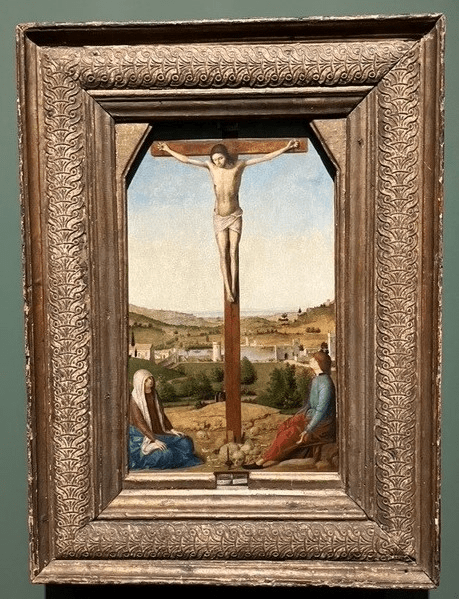

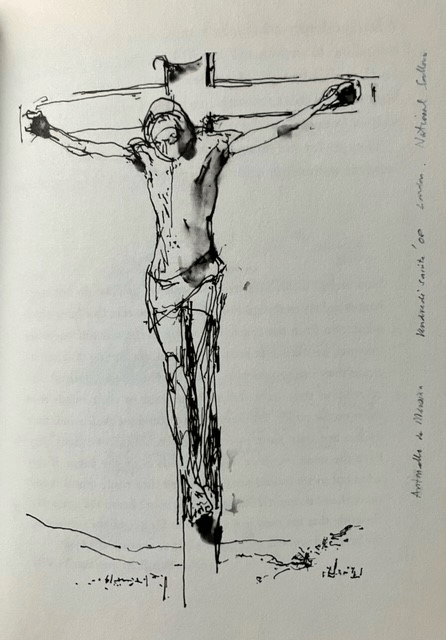

In one of my favourite books of his, Bento’s Sketchbook (Verso, 2011), arguably his last masterpiece, John Berger recounted, on pages 49–56, an incident in which, in 2008, he was ejected from the National Gallery by security guards for refusing to pick up his bag which he’d put on the floor while he sketched Christ Crucified, painted in 1475, by Antonello da Messina; one of three Antonello crucifixions (the others are in Antwerp and, curiously, Sibiu in Romania) it seems, though Berger said four.

Berger stated, on p.49, that, ‘It’s the most solitary painting of the scene that I know.’ He also wrote, on p.50, that:

What is so striking about the heads and bodies he painted is not simply their solidity, but the way the surrounding painted space exerts a pressure on them and the way they then resist this pressure. It is this resistance which makes them so undeniably and physically present.

A fortnight ago, in central London to meet a poet–friend later, I was the second person in the queue to get into the National a few minutes before 10; swiftly made my way into the Sainsbury Wing and found the Crucifixion more easily than I thought I would. There is of course something indescribably wonderful about coming face-to-face with great art. In this instance, it wasn’t so much the face or figure of Christ which drew my attention but the (Sicilian?) landscape beyond, and then the face of St John the Evangelist looking up from beneath his fashionable Renaissance haircut. Maybe the latter was modelled on a patron or their son. In 1475, Antonello was in Venice and aged about fifty.

In all, the National’s collection includes four paintings attributed to Antonello, including his Wunderkammer-containing St Jerome in His Study (1474) – in which, unlike other representations of Jerome, the lion with which he is traditionally prominently associated lies in the shadows – plus one possible. My favourite of them is his Portrait of a Man, widely assumed to be a self-portrait, in which intelligent eyes look almost sideways at the viewer from under a pair of solid eyebrows.

The joy of being early into the gallery was that most of the tourists had headed off to see the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, so I had whole rooms of Renaissance and Dutch Golden Age paintings to myself. It must be five years since I was last in the gallery, whose collection I know better than any other. With every visit, the humanity of Rembrandt’s portraits – especially of Margaretha de Geer and himself – has deepened for me over the years.

A bonus this time was a special feature built around the recent acquisition of Liotard’s 1754 pastel version of The Lavergne Family Breakfast, his beautiful rendering of an aunt watching her niece dunk bread in milky coffee. Twenty years later, he painted the picture again, this time in oil. I’d encountered Liotard’s pictures before, at the RA, but knew little about him, certainly not that he grew a long beard, dressed like a Turk after four years of living in what was then Constantinople with his patron Lord Duncannon, and became the talk of London society.

Coincidentally, in the Liotard room (the Sunley) I had the opposite experience to Berger: unprompted, one of the security guards happily engaged me in friendly conversation. But then at no point had I put my shoulder bag on the floor.

Leave a comment