I read Kathleen Jamie’s first two collections of nature and travel essays – Findings (2005) and Sightlines (2012) – when they appeared and loved them both. But they weren’t so much nature or travel essays as uncategorisable, touching on humankind’s relationship with nature, both mutual and destructive, rather than aspects of nature itself. You might say that they were as anthropological as anything. Her third essay collection, Surfacing (Sort of Books, available here), was published in 2020 but I’ve only just got round to reading it. What a deferred pleasure it was. Passing into middle age had evidently deepened Jamie’s already considerable philosophical grasp of time, ancestry and rootedness, as she wrote about places and peoples at what ‘civilisation’ might regard as the edge of things:

Transformation is possible. A bear can become a bird. A sea can vanish, rivers change course. The past can spill out of the earth, become the present.

(‘In Quinhagak’)

But Jamie is no wide-eyed truth-seeker ready to swallow other cultures’ wisdom unconditionally, and puts enough distance to enable the reader to intuit her strength of feeling. As one might expect from such a first-rate poet, Jamie’s writing is often beautiful. It’s now 32 years since her first non-poetry book, The Golden Peak was published (reissued in 2002 as Among Muslims, subtitled ‘Meetings at the Frontiers of Pakistan’), so a rate of one every eight years seems to me to be just about right.

I’ve recently read another prose work by a poet, although one better known for his prose than his poetry: Common Ground by Rob Cowen (Hutchinson, 2015, reissued by Windmill Books, 2016). I started it a year ago, then stopped because I couldn’t get into it. A blurb on the back by Alan Bennett no less – ‘[A] cracking book and having finished I now feel deprived’ – eventually drew me back in. It’s essentially the story of Cowen’s return to a village near Harrogate and his exploration of the edgelands thereabouts, with a background ‘plot’ of his partner’s pregnancy and birth. His prose is at times as dense as the thickets and brambles which crowd those edgelands. I was particularly impressed by one sub-chapter, part II of ‘The Union of Opposites’, in which he takes on the first-person persona of one John Joseph Longthorne, to tell his imagined life-story as

the youngest of four brothers but the only one blessed with cheiloschisis. People tell me that the preferred term nowadays is ‘cleft lip’, but back then even facial surgeons called it a harelip. In the end it doesn’t matter how you dress it up, it’s the same thing: a fissure, a rift in the tissue of my labium superius oris that happened before I was even born, a non-union that occurred in the womb.

That brief, 19-page story leads me to think that if and when Cowen ever writes a novel it will be tremendous.

I can’t pretend that I didn’t find some of the edgelands descriptions a bit hard-going and I didn’t emerge from the book with the same sense that Little Alan did. Neither did I feel that it deserves its status as one of the best ‘new nature’ books yet to be written; nevertheless, I could see why people liked it.

I had the same sort of feeling when at last I finished Spent Light by Lara Pawson, which has been sitting on my bedside table since I started reading it back in May. Somewhat oddly, it’s been nominated for the 2024 Goldsmiths Prize, whose statement of intent is as follows:

The Goldsmiths Prize was established in 2013 to celebrate the qualities of creative daring associated with the University and to reward fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibilities of the novel form. The annual prize of £10,000 is awarded to a book that is deemed genuinely novel and which embodies the spirit of invention that characterises the genre at its best.

Although the publisher, the estimable CB Editions, categorised it as ‘fiction / memoir / history’ on the back cover, Spent Light felt more like a series of reminiscences and vignettes rather than mould-breaking fiction. It had its moments; somehow though it wasn’t for me. One benefit of reading it was that Pawson raved about White Egrets by Derek Walcott, a collection which has been sitting on my shelves unread for a few years, so I’ve now started reading it.

When Fleur Adcock died the other week, there were many comments about how she was the last UK-based poet of her generation and every time I saw words to that effect, I wanted to shout, What about Ruth Fainlight?’ Fainlight was born in 1931, three years before Adcock, and is still with us. A few weeks ago, I bought and read a copy of her 1976 collection Another Full Moon and enjoyed it immensely. Her poem ‘Ghosts’ begins:

Old men, women, ancients, old crones,

Jealous and interfering ghosts;

Ancestors with their accusations,

Who know best where to place each wound,

Who, fierce and unforgiving, lap my tears,

Thicken the cries in my throat.

I was bound to be predisposed towards her given the fact that she was married to Alan Sillitoe, the first writer for adults I ever read; however, I wasn’t expecting to like her poetry as much as I did. I think I may have heard her read back in the 1980s, possibly on the bill for the all-day extravaganza at the Royal Albert Hall in 1984. One of her most well-known poems ‘Handbag’ is one of her four poems on the Poetry Archive website, here.

I re-read Sean O’Brien’s The Drowned Book (Picador, 2007), which won both the Eliot and the Forward, and loved again its wit and erudition, and admired especially two elegies, a sonnet for (and named for) Thom Gunn and a longer poem for Ken Smith. That was by way of a warm-up for the pleasure of reading his 2015 collection (also from Picador), the drily-titled The Beautiful Librarians. It includes such gems as the marvellous title poem, about ‘The ice-queens in their realms of gold’; ‘Nobody’s Uncle’, in which the eponymous anti-hero ‘might be taken for a fisherman / Who sets out more from habit than belief’; ‘At the Solstice’, with its killer line ’As daylight turns to cinema once more’; and the arcane strangeness of ‘Grey Rose’, which ends thus:

The grey rose is and cannot be.

It neither toils nor spins. It waits.

A truth that will not set you free,

Grey rose that’s nothing but a rose

That flowers here where nothing grows.

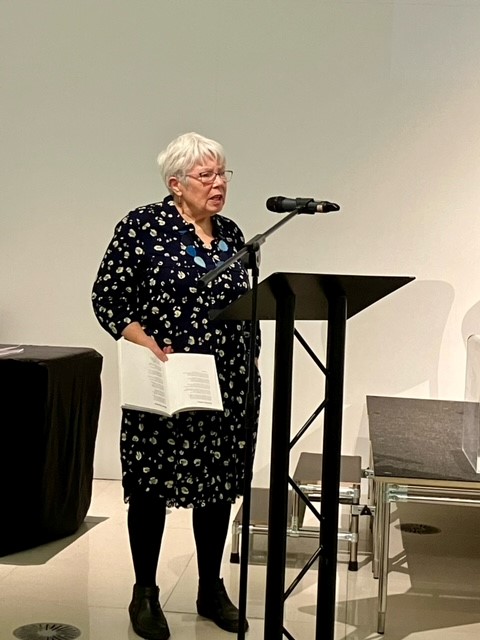

Last Wednesday, I attended an Off the Shelf Festival event in Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery: readings from the new SmithǀDoorstop anthology, Coal, edited, though not credited as such, by Ann and Peter Sansom and Sarah Wimbush, to mark the fortieth anniversary of the 1984–5 NUM strike. Peter Sansom, Wimbush and Ian Parks read poems, as did a few other contributors, including Alan Payne, Sue Riley (pictured below), Laura Strickland, and Tracy Dawson, whom I’ve got to know through Parks’s Read to Write group in Doncaster. It was a super event and the book – available here – is even better, containing as it does not just brilliant poems, but also prose, and photographs from the strike.

Now I’m immersed in reading books which I’m due to review. As chores go, I can’t think of anything finer.

Leave a comment