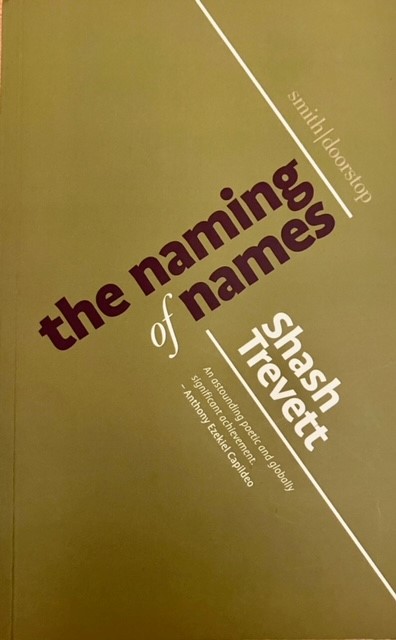

Shash Trevett’s debut full collection, The Naming of Names, published by the Poetry Business and available to buy here, follows on from her 2021 pamphlet From a Borrowed Land, with more poems relating aspects of the Tamil experience of the civil war in Sri Lanka between 1983 and 2009 and some on other, ancillary matters: British colonialism and racism (including that of the UK government’s immigration policies). Readers may also know that Trevett was one of the three co-editors of the exemplary and acclaimed Out of Sri Lanka anthology, published by Bloodaxe last year.

Estimates, disputed by the state’s Sinhalese majority, suggest that more than 100,000 Tamil civilians died during the conflict, many as victims of brutal violence, including sexual violence, bombings, massacres and/or dismemberments. As the title indicates, Trevett’s collection aims to put names to some of those victims, to reanimate them as real people, so that they aren’t just statistics. As a refugee from the war herself, Trevett writes with understandable passion, though in spare language which allows the individual and collective stories and incidents to speak for themselves without embellishment. It’s necessarily a difficult read, as any bearing of witness to war crimes is, as in ‘And on the Ceiling, a Lizard’:

When he rested his gun against the wall

and told me to lie down.

When he placed a grenade by the pillow

and unbuckled his belt

I watched the dust motes hang

in the air and the lizard freeze

on the ceiling, and knew that words

had never had the power to save me.

This almost matter-of-fact recounting magnifies the terror far more than any liberal sprinkling of adjectives could do. It’s hard in reading this fine collection not to think of Gaza, Sudan and other places where State-inflicted warfare inevitably kills thousand of civilians as collateral damage. Above all, though, it shines a light on what very specifically happened to the Tamil people, the ramifications of which are naturally still being felt. (When I worked for Kingston Council, in the Student Awards team, in the early 1990s, I saw a good number of customers who were Tamils living in exile in Tolworth and some of whom revealed the circumstances of what they’d seen. That Tamil community is still going strong.) This brave, elegantly crafted collection doesn’t flinch from the horrors, yet somehow also finds a sense of beauty among them:

[. . .] The last mango tree

waits, remembering those years when children

clung to its branches, women picked its fruit –

green for pickling, honeyed orange for eating.

The last mango tree knows that its branches

hold the secrets of a lost people.

It stands guarding memories, surrounded

by abandoned and derelict life.

(‘The Last Mango Tree’)

I’ve written about Robert Hamberger’s poetry before, in a review for The North of his 2019 collection, Blue Wallpaper; I concluded by saying that, ‘It’s high time that Hamberger becomes widely acknowledged as the marvellous poet he is.’ His new, fifth collection, Nude Against a Rock, published by Waterloo Press and available to buy here, amply justifies my belief that Hamberger is a highly gifted poet.

It’s a bumper collection, stretching to 100 pages, yet it doesn’t feel over-stuffed. That may in part be because most of Hamberger’s poems are fairly short, including lots of his trademark exceptional sonnets, which he always turns with a naturalness belying the constraints of the form; but more, though, because they always have a discernible point to them. The first section contains 17 poems about his husband, such as the terrifically-titled and tender ‘Love Song for a Bigot’:

If whatever I do tonight

makes you shudder you don’t need

to watch. When I kiss his eyebrow

his shoulder his dick it’s none

of your business. I claim sanctuary

in his arms. My door is bolted.

I’m an eel and he’s my river.

The middle section, of 46 poems, is more miscellaneous: here we find, inter alia, poems for and about his children and grandchildren; recollections of his father and mother and of old, departed friends, including Mark Hollis of Talk Talk, and his aunts who so memorably featured in Blue Wallpaper also. There’s also a sonnet called ‘Street Song’ – presumably a nod to Thom Gunn’s poem of the same name, though the two poems’ subjects are very different – which seems to be in the voice of a homeless person: ‘Who owns me? Who chose / to call me mister when time’s harder / than ten pavements and I need no sparrows / whistling for my crumbs?’

The final section has the same name as the book’s title, deriving from a painting by the gay artist Keith Vaughan, 1912–1977. Its 28 poems respond to selected journal entries of Vaughan’s, from August 1939 up to his suicide by an overdose after two years of living with cancer, and/or other writings and artworks. Sequences can often feel too forced in places, but this doesn’t, as Hamberger fully inhabits Vaughan’s voice and creative mind, at times thrillingly:

You leap into paint:

its scuffs and strokes and splashes –

gouache seems a caress on paper,

oils a sticky glut, ink and wash

thunder and cloud. They make a man

of you, this body of contradictions

standing barefoot by the easel.

You leap over naysayers, the obstructers,

your damned neurosis, foggy doubt.

You leap over courts of justice,

steeples in autumn villages,

your mother’s grip, your lover’s smothering.

(‘Leaping Figure’)

He also convincingly ventriloquises Vaughan’s despair towards the end:

Shall I drink now from the yellow cup,

let rainfall soak a broken lip

a parchment tongue –

stream into my hands until

I’m overflowing? Look how this slate

edge balances green,

how empty my hours have become –

like a jug loses purpose when the pouring’s done.

(‘Still Life with Greengages and Yellow Cup’)

As I noted four years ago, Waterloo Press’s production values are superb, perhaps the best of any poetry publisher in the UK, and in this case they perfectly augment the satisfaction which the reader gains from the tremendous contents.

I’ve also read two more Rupert Thomson novels: The Book of Revelation (2000) and Never Anyone But You (2018). The more I read Thomson’s books, the more he reminds me of Brian Moore, whose novels spanned a vast range of subjects, narrative voices and styles, but never less than compellingly; and like Moore knew, Thomson also knows how to write proper page-turners. Given that my attention span for prose is much lower than it used to be, that fact is increasingly important!

To give a flavour of the plot of The Book of Revelation would be to ruin it, so suffice to say that its plot twists and first-person psychological insights are engaging throughout.

Never Anyone But You is also written in the first person, in the voice of Suzanne Malherbe, AKA Marcel Moore, and recounts the lives and deaths of Moore and her lifelong partner, Lucy Schwob, AKA Claude Cahun. As is increasingly well-known, both Moore and Cahun were avant garde, multi-talented creatives who chose to live their unorthodox, gay lives openly. I loved this line:

The longer you’re with someone, the more mysterious they become.

Moore and Cahun’s finest moments arguably came during the war when, living on Jersey, they defied the Nazis for four years by spreading propaganda leaflets designed to demoralise the occupying forces, until they were betrayed to the Gestapo. Thomson’s version of their story is really quite beautiful and evidently painstakingly researched. Thomson’s output is yet to garner any literary prizes whatsoever, which is mystifying. Hey ho.

Leave a comment