I have Helena (Nell) Nelson to thank for this, and for permission to quote from her writing. A while back, I was looking through past issues of The North and came across Nell’s appreciation of the poetry and prose of Anna Adams (1926–2011) in issue no. 47, 2011. Nell’s interest had been piqued by the poet and editor John Killick. Unfortunately, as Nell remarked at the start of her piece, ‘Good poets get lost’, a theme to which the conclusion winningly returned:

Anna Adams is not lost. She is here, waiting to be found where she has always been, between the lines of her poems. The space she creates there is like the Tardis: what first looks small gets bigger as you enter. Once you have been in, you come out changed, remembering, as though for the first time, that true poetry is like nothing else, like nothing else at all.

It was with those words in mind that I bought a copy of Adams’s 1986 Peterloo Poets collection, Trees in Sheep Country. Almost all the poems are nature poems, set in and around Horton in Ribblesdale, in the Pennines in the north-west corner of North Yorkshire, not far from the Lancashire and Cumbria coast and close to Brigflatts, to which Basil Bunting added an extra ‘g’ for his supreme extravaganza of the same name. More importantly, they are wonderful poems, i.e. full of wonders. Take, for example, the first four (of nine) stanzas of ‘Rearing Trees in Sheep Country’:

Sheep are tree-wolves. Even the hare attacks

in snow, and gnaws the bark far from the ground,

recording height of drifts, but seldom rings trees round

and doesn’t hunt the rooted flock in packs.

But in late February, belly’s trouble

drives the sheep wild. Though bulging big with lamb

they scramble over walls and topple them.

Where one stone falls, soon a wide gate of rubble

welcomes the eager rabble. Our young trees

are sweet as sugar-sticks with rising sap,

and tempt the sheep as a self-service shop

tempts children. Rubber lips stretch up and seize

horse-chestnut toffees, tear smooth twigs of beech

whose curving fingers beckon towards spring;

grey mouths emulsify mute promising

of intricately folded summer speech.

This, I think, exemplifies Nell’s astute observation that, ‘[Adams] knows how to play, how to pursue a thought through beautiful syntax.’ I especially like the wit in the third stanza; and how all the precision is contained within a framework of a fine, unobtrusive rhyme-scheme and an almost always regular syllable-count. That last clause sounds on the ear as gorgeously as any sweet treat would melt in the mouth.

A poem by Adams was ‘Poem of the Week’ in the Guardian in 2011, here. I will be seeking out more of her publications, rare though they may be.

I like the fact, too, that John Killick passed on his enthusiasm for Adams to Nell, who in turn did so to me. Now I’m doing likewise to you, kind reader.

-

On Anna Adams

-

On Patience Agbabi’s Bloodshot Monochrome

Back in December 2022, I sang the praises, here, of Jackie Wills’ SmithǀDoorstop book, On Poetry*, and noted the excellence of her exegesis of Patience Agbabi’s superb ‘The Doll’s House’, a poem written in ‘rime royale’; 12 seven-line stanzas, each in an ABABBCC pattern, originated by Chaucer and used by Spenser, Yeats and Auden among others. The poem slowly but surely nails Britain’s terrible culpability for its colonial crimes and practice of slavery, the horrors and legacy of which it, as a sovereign state, is yet to acknowledge fully, let alone provide any restitution for.

So I thought, a month or two ago, that it was time to read some more of Agbabi’s poetry, and I bought her 2008 collection, Bloodshot Monochrome, published by Canongate and available here.

It has an arresting cover, in orange, red, black and white, but it’s let down by being printed on the sort of low-quality paper which Puffin Books used in the Seventies. Thankfully, though, the poems don’t disappoint. As ‘The Doll’s House’ demonstrated, Agbabi is a brilliant, sometimes offbeat formalist poet, and there are, inter alia, many fine sonnets in the book, concluding with a 14-sonnet sequence, ‘Vicious Circle’ which unfolds a Noir-ish tale of dangerous desire; an unorthodox crown of sonnets of sorts. As much as her subject-matter and viewpoint, it’s Agbabi’s play with form which makes her poems stand out..

A series of seven dramatic monologues really grabs me, including ‘Skins’, chosen by Carol Rumens in 2016 as a Guardian ‘Poem of the Week’, here. As Rumens notes, it’s a sestina, but with short lines, meaning that it doesn’t drag on wearily and underwhelmingly like many sestinas do. Over the years, I’ve had the occasional tussle with myself about the ethics of dramatic monologues, and which voices it is acceptable to adopt and which not. Those Agbabi inhabits are fine and entirely believable. My favourite is ‘Heads’, in which Thomas Cromwell sardonically, and post-mortem, digresses from the appearance of Anne of Cleves to a discussion of axe-wielding executioners:

My fate was set. For Anne Boleyn he hired

the best from France; for me a beardless boy.

Be not afraid, I said, pray, take this gift.

’Tis all I have. Both of our hands were shaking.

I prayed aloud. The crowd, an army shrieking

Traitor! Its face degenerate with hatred.

* I recently re-read On Poetry and found it as illuminating and helpful as I did the first time round.

-

On Doreen Gurrey’s A Coalition of Cheetahs

I was recently asked to provide some blurb for Doreen Gurrey’s Poetry Business International Pamphlet Competition-winning, A Coalition of Cheetahs. It’s a super read, and I described it thus:

How skilfully and humanely Doreen Gurrey’s poems depict whole worlds. Here are sharply-sketched portraits of family members; inquisitive cows and fiercer creatures; keepsakes both precious and not; incidents both comic and dark; the love of Gwen John for Rodin – and among them all, the ‘hiss and kiss’ of life, in York, Spain and elsewhere, as refracted through the clearest lens.

The online launch can be viewed on YouTube, here (Doreen’s reading starts just after the 58-minutes mark), and the pamphlet is available to buy here.

-

On a poem by Siobhán Campbell in Poetry Wales

It might seem odd that, not having eaten meat since 1982, I should become obsessed with something so very meaty, but Siobhán Campbell’s poem ‘Rump’ in the latest issue of Poetry Wales is just the sort of superb poem which floats my boat, grounded as it is in the strangest reality. In that respect, it reminds me of the output of some other Irish writers I love: Martina Evans, Matthew Sweeney, Flann O’Brien, even Patrick McGinley.

I’d quote from it, but really the poem needs to be read in its entirety. If you don’t subscribe to Poetry Wales, then maybe you should, here.

-

Review of Mike Barlow’s A Land Between Borders

With thanks to Hilary Menos and Andy Brodie, my review of Mike Barlow’s latest collection, A Land Between Borders (Templar Poetry), is in this week’s edition of The Friday Poem, here.

-

Michael Hamburger’s centenary day

Today. I doubt Hamburger would’ve wanted much fanfare, but I can’t let it pass.

His 2000 collection Intersections (‘Shorter Poems 1994–2000’) included, on facing pages, two of his loveliest poems, ‘Spindleberry Song’ and ‘Swans in Winter’. The final two quatrains of the first provide another example of Hamburger’s earth-rooted melancholy:

Fallen leaves, let them stay

Where they stopped, weighed down with rain.

From the season for lying low,

Get up if you can.

But time’s the mere measurement

Of motion, mutation in space.

Unbleeding though bare from this plant

Hangs the heart-shaped seed-carapace.

‘Swans in Winter’, though, is a beautiful affirmation:

Has their long marriage ended? On pastures separated

Less by our culvert than their chosen distance,

Composure that seems indifference to our eyes

While each unhuddled picks at low herbage, grasses,

Their slow necks rippling as though no fang, no weather

Could ever so much as ruffle the silk it wears.

I especially like that ‘unhuddled’, and how he presents it without commas either side, the effect of which is to change the word into a noun. Making nouns into adjectives (or verbs) is common poetic practice, but to do the reverse, other than by sticking a definite article in front, is, to my mind, very rare.

*

2004’s Wild and Wounded (‘Shorter Poems 2000–2003’) continues seamlessly from Intersections. Its finest poem, perhaps, is ‘A Cat’s Last Summer’. As the title suggests, it’s a study of old age, by a poet deeply aware of his own mortality and, with that mention of Belsen, of how his life could so easily have been ended before it had barely begun. Most of all, though, it’s a wonderfully tender series of observations, all the more affecting because of the outward absence of emotion:

Day after day she sits

On the same patch of grass,

Her senses waning, the well-deep eyes enlarged

But not for seeing,

Her needle-sharp hearing blunted;

And Belsen-thin, ribs showing through,

So fearless now that when a cock pheasant

Struts at her, clucking, claims the terrain,

She neither deigns to flee

Nor make to spring, as she could,

Agile enough, did a will impel her.

How he conjures as ‘fearlessness’ the cat’s reluctance to see off, or catch, the pheasant is remarkably astute.

*

Each of the poems extracted here need to be read in full and I much recommend tracking down copies of the Anvil collections, or at least the Carcanet reader, edited by another tremendous Anvil poet, good old Dennis O’Driscoll, and which is available here. The engaging, exceptional existential clarity of his poetry richly merits celebration.

-

January–February reading

Not that I’m suddenly verse-averse, but my reading so far this year – Hamburger, James Tate and Mike Barlow aside – has been largely dominated by prose books.

Two were Sebald-related: The Emergence of Memory, a collection of interviews with and writings about him, edited by Lynne Sharon Schwartz, and Philippa Comber’s extraordinary memoir, Ariadne’s Thread. As with all Sebald literature, there are many quotable lines and astonishing moments.

I’ve frequently had the same experience when reading Claudio Magris’s 1986 masterpiece, Danube, as translated by Patrick Creagh, a book I was alerted to because it was mentioned in Comber’s.

While it’s superficially a journey from the Danube’s several contesting sources to its delta entry into the Black Sea, it’s far more than that: Magris’s knowledge of Mitteleuropa history and literature is remarkable. Here are two short, separate extracts which I noted down:

Perhaps writing is really filling in the blank spaces in existence, that nullity which suddenly yawns wide open in the hours and the days, and appears between the objects in the room, engulfing them in unending desolation and insignificance.

Time is not a single train, moving in one direction at a constant speed. Every so often it meets another train coming in the opposite direction, from the past, and for a short while that past is with us, by our side, in our present.

I gather that it was brought back into print a couple of years ago – and I should think so, because its digressions, even when addressing some of the worst of Nazi horrors, are always remarkable. Sebald must’ve read him, for they are surely kindred spirits and stylists and they share an obsession with Kafka, though Magris is much the funnier.

Another writer mentioned in the Comber book was Sara Maitland, whose books I had long been meaning to start reading. Start I did, with her lovely book on the woodland roots of fairy tales, Gossip from the Forest. Like Danube, it’s full of erudition, with the bonus of the chapters being separated by her own retellings of classic fairy tales.

Among novels, I very much enjoyed the twists and turns of Case Study by Grahame Macrae Burnet and Katherine Carlyle by Rupert Thomson – two brilliantly written and absorbing tales. (I know I’m late to the party, but I’ve just started the latter’s The Insult.) I also read Here We Are by Graham Swift, but it really dragged.

Lastly, there’s Patrick Barkham’s The Swimmer, subtitled ‘The Wild Life of Roger Deakin’, an unconventional biography of a very unconventional man. I’ve written about Deakin before – here and here – because I’ve been a fan since Waterlog was first published. Like all the best biographies of writers, it’s made me want to re-read its subject’s oeuvre. I enjoyed it so much I read it in one day.

-

New poem – ‘Deauville, 1999’

I’m very pleased to have a poem in a fine new journal, The Fig Tree, edited by Tim Fellows, available here. Each issue will have a featured poet; this time it’s admirable Ian Parks.

-

On Michael Hamburger reading his poetry

Thanks to the Poetry Archive, Michael Hamburger’s bewitchingly lugubrious voice can be heard, here, reading three poems not long after his 79th birthday. It’s a meagre number for a poet of such a prodigious output, but never mind.

The first poem is an extract from his collection From a Diary of Non-events (Anvil, 2002), consisting of a year’s worth of monthly ruminations written, as he says in the recording, between December 2000 and November 2001. (‘Muted Song’ and ‘Ave Atque Vale’ were published in his 2004 collection, Wild and Wounded.) While much of From a Diary of Non-events consists of poeticised nature-notes, there are also some irruptions of memory, as in the opening stanza of part 1 of ‘April’:

Fools’ Day has tricked the diagnostic view:

A visible sun has risen

At the pasture’s far end from a scud

Not smoke but vapour released at last

From ground long sodden, puddled.

Out of that wispy whiteness contours emerge,

The whiter white and black

Of the Frisians grazing as ever,

Prodigious now as a Gipsy encampment surprised

In a German glade in April 1945,

A congregation of Jews untagged

In the centre of ruined Dresden.

Here too eugenics, the money-drive,

Doomed the defenceless breeds

To be slaughtered for purity by butchers mortal, impure.

For Hamburger, a German Jewish refugee, serving in the British Army at, and after, the end of the war and the Holocaust, must have involved such complex emotions. In his memoirs, A Mug’s Game, he says that he wasn’t posted abroad until June 1945, to Italy first and then Austria, but he also says that he destroyed his diaries from that time, so one can forgive him for getting his dates wrong – unless the details he related in this poem were not his own experiences. Either way, their inclusion more than hints, of course, at the most terrible of events and their desperate aftermath.

As ever, I admire how accurate Hamburger’s descriptions are, and how they steer clear of being oppressively so. I like, too, that eye-rhyme between ‘wispy’ and ‘Gipsy’.

-

On Hamburger, Hughes and Heaney

Tacita Dean’s superb 2007 film on Michael Hamburger features no dialogue until the last ten minutes or so, when Hamburger, at a wooden table, discusses the different varieties of apples which he has grown in the garden of his Middleton home. He mentions some apple seeds which Ted Hughes sent him and then reads the elegy, available here, that he wrote hard upon Hughes’s death. It’s the only poem in the film, and is consequently all the more intrinsic to the film’s power. I found the poem, especially its last stanza, very moving indeed; as I still find it when I read it on page 56 of his accessible but somewhat patchy collection, Intersections (Anvil, 2000):

Uneaten this day of his death

In either light the dark Devonshire apples lie

That from seed I raised on a harsher coast

In remembrance of him and his garden.

Difference filled out the trees,

Hardened, mellowed the fruit to outlast our days.

The last two lines seal the poignancy. Hamburger died shortly after Dean filmed him.

For all its flaws, Intersections also includes one of Hamburger’s finest poems ‘The Lean-to Greenhouse’, a masterpiece of English wabi-sabi, which opens thus:

Lightly it seems to wear its eighty years

By being there still, leaning

On a bracket of bricks that alone are sound

And at its apex depending

On a cottage wall four centuries old.

I love old greenhouses, and poems about them.

*

Temperamentally, as expressed in poetry at least, one would have considered Hughes’s unflinching view of nature to be more extreme than Hamburger’s gentler, more meditative approach. Hamburger’s words on Hughes in his survey of ‘tensions in modern poetry from Baudelaire to the 1960s’, The Truth of Poetry (Pelican, 1972), did nothing but state the obvious, with eccentric repetition of his full name:

In the work of Ted Hughes, [. . .] historical experience is inseparable from a new concern with the ferocity of predatory animals. Ted Hughes did not need to draw elaborate analogies between his hawk, whose ‘manners are tearing off heads’, and the human proclivities that have given him his peculiar power to identify with hawks, pike, thrushes, otters or water-lilies; the single word ‘manners’ is enough to make the connection. Even Ted Hughes’s snowdrop is ‘brutal’ in the pursuit ‘of her ends’.

By comparison, Heaney’s verdict on Hughes, as articulated to Dennis O’Driscoll in Stepping Stones, was more insightful and lyrical: ‘There’s Blakean recklessness in Hughes, the poetry of the living present, the shimmer of the gene pool and the galaxies.’ (He also calls Hughes ‘a poet of genius’.) But then Heaney’s criticism and his writings on the process of poetry, like his poetry itself, were peerless among his English-language contemporaries, so maybe the comparison isn’t really fair.

-

On Sebald and Hamburger again

In chapter VII of The Rings of Saturn, as rendered into English by Michael Hulse, Sebald’s narrative persona describes, after a battle to escape the ‘labyrinth’ of Dunwich Heath, his first visit to Michael Hamburger’s home in Middleton, Suffolk. He appears to quote some spoken observations of Hamburger’s verbatim, none perhaps more characteristically despondent (and so much so that they could be Sebald’s own words) than those in this sentence:

For days and weeks on end one racks one’s brains to no avail, and, if asked, one could not say whether one goes on writing purely out of habit, or a craving for admiration, or because one knows not how to do anything other, or out of sheer wonderment, despair or outrage, any more than one could say whether writing renders one more perceptive or more insane.

Sebald goes on to note several coincidences between the pair of them. (But then coincidences are easy to find: my father, also called Michael, was born in 1933, the cataclysmic year for Hamburger in which he and his family left Berlin for exile in Edinburgh, and did his stint of National Service in the same army regiment, the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent, as that in which Hamburger served in the last years of the war and just after; and Sebald lived, and is buried, in Poringland, Norfolk, barely nine miles from the village whence hailed generations of my mother’s maternal ancestors.) In a hallucination of sorts, Sebald almost sees Hamburger as another self:

But why it was that on my first visit to Michael’s house I instantly felt as if I lived there, in every respect precisely as he does, I cannot explain. All I know is that I stood spellbound in his high-ceilinged studio room with its north-facing windows in front of the heavy mahogany bureau at which Michael said he no longer worked because the room was so cold, even in midsummer; and that, while we talked of the difficulty of heating old houses, a strange feeling came upon me, as if it were not he who had abandoned that place of work but I, as if the spectacles case, letters and writing materials that had evidently lain untouched for months in the soft north light had once been my spectacles cases, my letters and my writing materials.

Sebald’s writings are chockful of Freudian examples of ‘Das Unheimliche’ like these. Sebald goes on, a few pages later, to air another uncanny sense:

Scarcely am I in company but it seems as if I had already heard the same opinions expressed by the same people somewhere or other, in the same way, with the same words, turns of phrases and gestures. The physical sensation closest to this feeling of repetition, which sometimes last for several minutes and can be quite disconcerting, is that of the peculiar numbness brought on by a heavy loss of blood, often resulting in a temporary inability to think, to speak or to move one’s limbs, as though, without being aware of it, one had suffered a stroke.

I read Sebald because I intuit that he, perhaps more than another writer I’ve ever read, aligned the dream state and consciousness, the dead and the living.

Without mentioning its title, Sebald’s narrator also refers in passing to Hamburger’s A Mug’s Game (Carcanet, 1973), subtitled ‘intermittent memoirs 1924–1954’. (Its title derives from Eliot’s description of poetry.) I first read the book about twenty years ago, having acquired it for 50p at a summer fair at my children’s primary school, and years on gave it to Oxfam, but I’ve recently bought another copy and re-read it. It’s a frustrating read in many ways, not least in that it stops when it does, at the point when he gave up the penury of freelancing for comparatively steady employment in academia. However, it has its rare moments of elucidation, such as this comforting passage:

As for the mug’s game of poetry, its pursuit has become harder and easier. Harder, because ambition, like every external incentive, has fallen away. Easier, because that loss is another liberation. I can be no more sure than I was thirty years so that my poems are good enough to be worth the price paid for them, by which I mean not the time and work that have gone into them but the specialization they demanded, the concentration claimed at the cost of other pursuits and commitments. What I am sure of now is that, whether good or bad, durable or negligible, the poems I write are those I have to write. The profession of authorship has no bearing on that. The opinions and judgements of critics have no bearing on that. Nor have the anxieties that used to beset me when I couldn’t write.

Curiously, Skoob, the marvellous secondhand bookshop in London, later, in 1991, re-published the memoir under a different title (which perhaps deliberately echoes the title of Louis MacNiece’s ‘unfinished autobiography’, The Strings are False), String of Beginning, the only addition being a postscript written, in late middle age, in 1990, in which Hamburger briefly reflected further on his vocation:

Whatever I may have done or known in my life, my poetry came out of a kind of wonderment whose other side – the left hand – is a sense of outrage. In general, too, this capacity to wonder, and to feel outrage, strikes me as a distinguishing attribute of poets, and a condition of their persistence in the mug’s game.Wonderment and outrage again. I can’t disagree.

-

On John Berger on Antonello da Messina

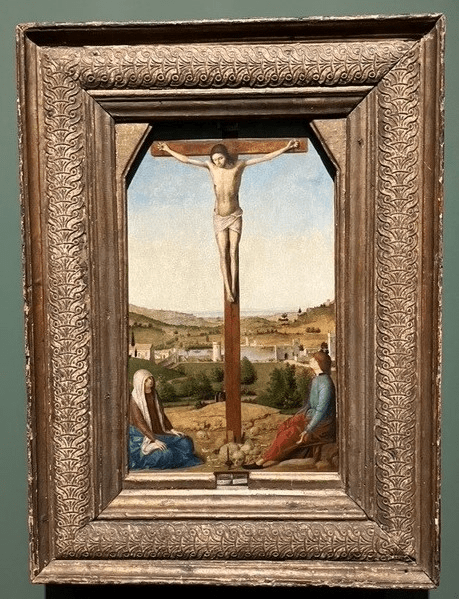

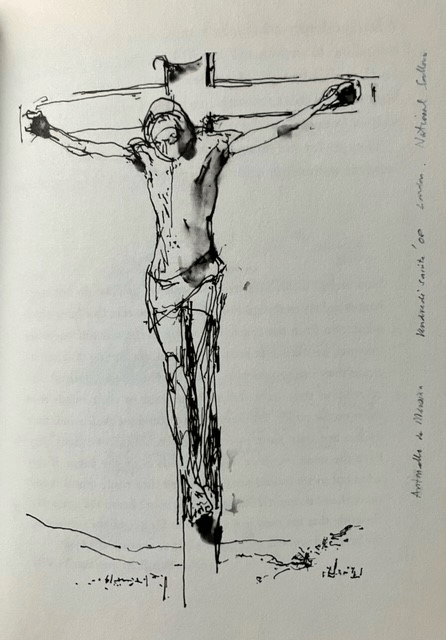

In one of my favourite books of his, Bento’s Sketchbook (Verso, 2011), arguably his last masterpiece, John Berger recounted, on pages 49–56, an incident in which, in 2008, he was ejected from the National Gallery by security guards for refusing to pick up his bag which he’d put on the floor while he sketched Christ Crucified, painted in 1475, by Antonello da Messina; one of three Antonello crucifixions (the others are in Antwerp and, curiously, Sibiu in Romania) it seems, though Berger said four.

Antonello da Messina, Christ Crucified, 1475 Berger stated, on p.49, that, ‘It’s the most solitary painting of the scene that I know.’ He also wrote, on p.50, that:

What is so striking about the heads and bodies he painted is not simply their solidity, but the way the surrounding painted space exerts a pressure on them and the way they then resist this pressure. It is this resistance which makes them so undeniably and physically present.

Berger’s sketch of Antonello’s Christ Crucified A fortnight ago, in central London to meet a poet–friend later, I was the second person in the queue to get into the National a few minutes before 10; swiftly made my way into the Sainsbury Wing and found the Crucifixion more easily than I thought I would. There is of course something indescribably wonderful about coming face-to-face with great art. In this instance, it wasn’t so much the face or figure of Christ which drew my attention but the (Sicilian?) landscape beyond, and then the face of St John the Evangelist looking up from beneath his fashionable Renaissance haircut. Maybe the latter was modelled on a patron or their son. In 1475, Antonello was in Venice and aged about fifty.

In all, the National’s collection includes four paintings attributed to Antonello, including his Wunderkammer-containing St Jerome in His Study (1474) – in which, unlike other representations of Jerome, the lion with which he is traditionally prominently associated lies in the shadows – plus one possible. My favourite of them is his Portrait of a Man, widely assumed to be a self-portrait, in which intelligent eyes look almost sideways at the viewer from under a pair of solid eyebrows.

The joy of being early into the gallery was that most of the tourists had headed off to see the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, so I had whole rooms of Renaissance and Dutch Golden Age paintings to myself. It must be five years since I was last in the gallery, whose collection I know better than any other. With every visit, the humanity of Rembrandt’s portraits – especially of Margaretha de Geer and himself – has deepened for me over the years.

A bonus this time was a special feature built around the recent acquisition of Liotard’s 1754 pastel version of The Lavergne Family Breakfast, his beautiful rendering of an aunt watching her niece dunk bread in milky coffee. Twenty years later, he painted the picture again, this time in oil. I’d encountered Liotard’s pictures before, at the RA, but knew little about him, certainly not that he grew a long beard, dressed like a Turk after four years of living in what was then Constantinople with his patron Lord Duncannon, and became the talk of London society.

Coincidentally, in the Liotard room (the Sunley) I had the opposite experience to Berger: unprompted, one of the security guards happily engaged me in friendly conversation. But then at no point had I put my shoulder bag on the floor.

-

In the footsteps of Larkin to Paull and Hedon

‘I’m sitting down after a quite busy though fairly enjoyable day – didn’t get up till 10.40 ogh ogh, then, it being a fine sunny morning, I got on my bike and went out eastwards: had a drink at Paull, a village on the Humber, & round through Hedon & home. About 30 miles in all. On the wall of the Paull pub there was a notice saying ‘old golfers never die, they simply lose their balls.’ Bucolic humour. A dull ride on the whole, but I felt in better shape – isn’t it odd that on Friday I was so feeble, just going to town tired me, yet today I could cycle a long way without feeling exhausted.’

Philip Larkin, letter to Monica Jones, 8 October 1961.*

7 August 2023

I take the train from Rotherham Central – misnamed now, as there’s no other station in the town anymore – to Doncaster for the connection to Hull. To my surprise, the Hull train’s already sitting there. It’s a lovely summer day. I arrive in the city just after noon, and walk the mile or two to the hotel where I’m staying, a former flour mill built in 1838, at a crossroads on Holderness Road.

The walk takes me past the vast Victorian City Hall and across the Drypool Bridge over the River Hull. The bridge, dating from 1961, is in the ‘Scherzer Rolling Bascule’ design – a drawbridge essentially, though I can’t imagine the liftable section is lifted very often, if at all – and is decorated with circles in honour of John Venn, he of the now ubiquitous diagrams, born nearby.

Once I’ve unpacked, I walk back into town, primarily to visit the Ferens Art Gallery. I love what were formerly called ‘provincial’ (and are now called the marginally less patronising ‘regional’) art collections, because even the smallest of them have unexpected treasures. The Ferens includes a beautiful Hals portrait, of a young, smiling woman, face-on to the painter and viewer; two Canalettos (one on loan); Atkinson Grimshaw’s extraordinary, green-tinged view of Whitby by moonlight; and Stanley Spencer’s gratuitously meaty nude of his second wife, Patricia Preece.

Preece tempted randy Stanley away from his first wife, Hilda Carline, by always being barely clothed whenever he visited her and then, once they were married, went on ‘honeymoon’ with her partner Dorothy Hepworth and refused ever to sleep with Spencer. Hepworth was a talented painter whose output Preece passed off as her own. Preece later talked Spencer into signing his house into her name. She’d long been a bit of a wrong’un, having inadvertently caused the drowning of W.S. Gilbert in a small lake in Harrow when she was 17 and known by her birth-name of Ruby. The other witness to the incident was Winifred Emery, who later became an actor and the mother of Britain’s finest Surrealist poet, David Gascoyne. Some time in the late 1980s, my mother and I visited the Royal Academy’s ‘British Art in the 20th Century’ exhibition: she, a doyenne of the Mothers’ Union, was less than enamoured by Spencer’s ‘Double Nude Portrait’ of 1937, also known as the ‘Leg of Mutton Nude’ in which said piece of meat foregrounds full frontals of both Spencer and Preece. Mum’s full ire, though, was turned on a Gilbert and George picture on which the word ‘wanker’ was emblazoned in huge capitals.

Returning to the hotel, I detour past Hull Minster.

Hull Minster The six-o’clock sun fills its sandy-coloured facade such that its grandeur, and setting on Trinity Square, reminds me of John Wharlton Bunney’s crepuscular painting of St Mark’s, Venice, in the collection of Ruskin’s Guild of St George in Sheffield. On a plinth in the square stands a life-size statue of Andrew Marvell, whose father was a ‘lecturer’ in the church until he drowned when crossing the Humber.

Statue of Andrew Marvell Later, I plod down Holderness Road into East Hull, and pass Rank House, birthplace, in 1888, of J[oseph]. Arthur Rank, founder in 1937 of the Rank Organisation, famous for the strongman striking a gong at the start of all their films.

Rank was a staunch Methodist, but profit came before faith so the company’s films weren’t always ‘family-friendly’. He was also a governor of the Peckham Experiment, a pre-war exercise in advanced social living, in which 950 families were encouraged to organise themselves as one community in a generally creative manner. Efforts were made to revive it after the war, when Lady Mountbatten was also a governor. It still exists, of sorts, as the Pioneer Health Foundation. Unlike most interwar do-gooding social studies, it seems not to have been a hotbed of fascists rounded up under Regulation 18B. (When, incidentally, The Times printed the news of Mosley’s internment, a keen-eyed reader wrote in to remark gleefully that the report had appeared in the particular page’s fifth column.)

*

8 August 2023

Instead of taking one of the many buses going in the right direction, I rashly decide to walk to Paull. From a new pedestrian path, I spot Hull Prison, dating from 1870; its mint-green roof complementing the Hampton-Court-like brickwork. If there’s one place where lead roofwork ought to be safe from thieves it’s here.

All along Hedon Road, large Port of Hull signs inform drivers that they’re ‘Keeping Britain trading’ – or as well as they can post-Brexit.

The village of Paull is round the bend at the end of a long, straight road and is largely strung out in parallel to the estuary.

Long grass, ragwort and ice-cream-coloured sea bindweed sway in the shoreline breeze. The river’s browns churn into blues with the movement of the clouds: ‘Here silence stands / like heat’.

The Humber estuary White paint is peeling off the Old Lighthouse, one of the earliest built by Trinity House, in 1826. With full late-morning sun on it, it’s a gorgeous building. The view, across to the Humber Bridge, must be fine from its balcony.

The Humber estuary and Humber Bridge

Paull lighthouse – frontal view

Paull lighthouse – side view I know in advance that it’s no longer open to the public as an attraction, but I can’t resist vising Fort Paull, a battery, originally built in 1542 and a century later used by Royalist forces, though the parliamentary ships easily evaded its guns in the great width of the Humber.

Fort Paull It saw service in both world wars and was decommissioned in 1960. Today, it’s overgrown and is occupied solely by house martins that swoop low over the adjacent field.

All the walking has whetted my appetite for a beer. It’s unclear which of the two pubs in Paull Larkin patronised, yet only one, the Humber Tavern, survives.

Paull I tip up at 11 to find the door shut and no lights on. After much sulking, I notice the small piece of paper in the window saying that it opens at 5pm on a Tuesday, which today happens to be. My disappointment mutates into happiness at the thought of the imminent arrival of the 79 bus to Hedon, where surely a pint can be had.

The driver’s a Cockney, wearing a West Ham lanyard. I’m the sole passenger and I climb the stairs to obtain some long views of countryside which could easily be mistaken as French, Belgian or Dutch.

In Hedon, I waste no time in heading up the town’s high street, St Augustine’s Gate, named after the impressive church, the ‘King of Holderness’ (St Patrick’s in Patrington, where I once took shelter in the porch from a torrential downpour, is the ‘Queen’) and which Pevsner described as ‘a reminder of Hedon’s former importance’. In his 10-quatrain poem, ‘A Bridge for the Living’, commissioned for the cantata celebrating the opening of the Humber Bridge in 1981 and written seven years since his previous poem, Larkin wrote, ‘Tall church-towers parley, airily audible / Howden and Beverley, Hedon and Patrington’.

St Augustine’s, Hedon My choice is between the Queen’s Head or the King’s Head further on. Two sips into a terrible pint in the latter and I wish I’d gone to the former. In the beer garden, I sing along to ‘Up the Junction’.

I mosey off for a circular wander which takes me to the ‘Shakey’, the Shakespeare Inn. Here, an old, bearded fella calls across to two other old boys, ‘I’m sixty-six, you know. Just qualified for my state pension.’ The reply is lightning-quick, ‘I’d’ve put you older than that.’ To which the first replies, ‘Would you? Well, if I shave this off . . .’

In the garden out the back, I tuck into a pint of locally-brewed Sleck Dust, a ‘straw-coloured’ blonde beer that hits a spot the King’s head beer could never reach. A wasp takes a liking to it too, repeatedly returning to the glass-lip. Another oldish man, carrying two pints, looks lost. His partner has not appeared. Ten minutes later, after much banter at his expense, she still hasn’t. ‘It’s like when you lose a dog,’ I venture. ‘You’re best off staying in one place and waiting for it to come to you.’ Turns out she’s helped a really old chap with a walking trolley make it to his front door up the road. Cheers all round.

I take the 75 bus, the service from Withernsea, back to Hull. The automated announcer says, ‘Next stop: Hull Prison.’ Do not pass go. The delightful 1932 East Hull Fire station has a motto painted above each of its three arched vehicle doors: ‘Ready Aye Ready’.

I get off at the interchange, next to Hull Paragon Station, location of both the well-known statue of Larkin and the Royal Hotel featured in his Symbolist-ish poem ‘Friday Night at the Royal Station Hotel’, completed in May 1966. In his biography of Larkin, James Booth claims that the atmosphere of the hotel is largely unchanged since the poem was penned, despite a major fire in 1990 and subsequent restoration.

It’s a sonnet, of course, with the turn coming after the ninth line. Although far from being the only poem in his oeuvre to prominently feature light, it starts with ‘Light’ and includes the word ‘lights’ twice, as though hammering the point that this hotel is, and maybe hotels per se are, very brightly lit: ‘In shoeless corridors, the lights burn.’ I love hotels, and I love poems, novels (e.g. Troubles by J.G. Farrell) and films (e.g. The Consequences of Love, Some Like It Hot and The Grand Budapest Hotel) which are at least partially set within them.

A curious part of ‘Friday Night’ is ‘all the salesmen have gone back to Leeds, / Leaving full ashtrays in the Conference Room.’ Few of Larkin’s mature poems mention smoking – is ‘Essential Beauty’ the only other? – even though he smoked throughout adulthood. In a dissection of ‘Cut Grass’, in which ‘Mown stalks exhale’, Tom Paulin conjured the perfect phrase, ‘the anxieties smokers know’; not all smokers are necessarily anxious (do Mick Jagger and Keith Richards ever get anxious?), but the overlap in a diagram by Mr Venn must be very considerable. All of this is a roundabout way of declaring my surprise that Larkin didn’t touch on smoking in his poetry more often.

The part of the poem which is undoubtedly the most intriguing is Larkin’s pressing-home of the point about the hotel being a bastion of ‘loneliness’ by adding the curiosity ‘How / Isolated, like a fort, it is’. Was he thinking of Fort Paull here? Or maybe Bull Sand, one of two Great War forts built in the Humber Estuary, visible from the end of Spurn Point, which is implicitly featured in ‘Here’ .

-

On Michael Hamburger on trees

When we consider English poets of the last century or so, few – if any – have surely written about trees as extensively, and as well, about trees as Michael Hamburger. In his short poetry career, Edward Thomas wrote the occasional tree poem, of which only ‘Aspens’, accessible here, partially attempts to get ‘inside’ the trees:

All day and night, save winter, every weather,

Above the inn, the smithy, and the shop,

The aspens at the cross-roads talk together

Of rain, until their last leaves fall from the top.

Then, of course, there’s Philip Larkin’s ‘The Trees’, read by Larkin here, which, despite its apparently wide appeal, is, to me, one of the least satisfying poems within his mature corpus – though that bar is high. As his best biographer, James Booth, notes, Larkin himself disparaged it as ‘very corny’ and even ‘awful tripe’.

One of Larkin’s great favourites, Hardy, wrote about trees solely in the context of chopping them down (‘Throwing a Tree’). Heaney wrote ‘The Wishing Tree’. But neither concerned themselves with the tree-ness of trees.

Hamburger devotes the whole of the first section – 15 poems – of possibly his richest collection, 1991’s Roots in the Air (Anvil Press) to trees, the first 10 of which each take a single species as their subject, e.g. ‘’Willow’, ‘Elm’, ‘Beech’, etc. ‘Fig’ opens thus:

London made this one: it germinated

On a compost heap, from a matrix

Desiccated and old –

Some fig-end chucked out as refuse;

From a flower-pot began its ascent into light,

A stowaway there, so strange, it was welcome

And planted out. Then dug up, transported

To a colder county, with gales from the North Sea,

Where, rooted in shingle, it took, and throve,

Put out great five-fingered leaves;

Barren, after ten years, but far from mature.

That punning ‘fig-end’ is irresistible; and no doubt Hamburger’s sympathy for the fig’s transplantation stems from his own at the age of nine.

In ‘Yew’, Hamburger addresses the size and long lives of individual trees and their propensity for growing in graveyards:

Too slowly for us it amasses

Its dense dark bulk.

Even without our blood

For food, where mature one stands

It’s beyond us, putting on

Half-inches towards its millennium,

Reaching down farther

Than our memories, our machines.

In ‘Oak’, a tree ‘alone looks compact, in a stillness hides / Black stumps of limbs that blight or blast bared; / And for death reserves its more durable substance.’ The poem’s ending is reminiscent of the writings of Roger Deakin, another Suffolk-dweller, who wrote extensively about trees, especially in Wildwood, and lived in an Elizabethan house with great, creaking beams:

How by oak-beams, worm-eaten,

This cottage stands, when brick and plaster have crumbled,

In casements of oak the leaded panes rest

Where new frames, new doors, mere deal, again and again have rotted.

Unsurprisingly, Hamburger also wrote, in the section’s last three poems, about the Great Storm, of 17 October 1987, and its aftermath. ‘A Massacre’ begins in an uncharacteristically Blakean vein,

It came like judgement, came like the blast

Of power that, turned against itself, brings home

Presumption to the unpresuming also,

To those who suffered power and those unborn.

Throughout Hamburger’s tree poems there is a deeply-felt admiration, both explicit and implicit, for the endurance of trees. ‘Afterlives’, documenting the extensive work undertaken in the storm’s wake, is positively Shakespearean in its register, ambition and rolling diction and its superb closing couplet:

Prostrate, the mulberry from half its roots,

Far less than half its wood of centuries,

Shoots again, grapples, twists

And on the old as on the new twigs bears

Fruit for the blackbirds, thrushes,

With luck a few for us;

Who now, more singly seeing, meet what remains,

Less than the tree it was and more than a tree

By the diminishment, the lying low,

Bedded on grass, with poppies and balsam lush

Where the shade was its greater prospering cast.

No wonder that in her film about Hamburger, Tacita Dean chose – with wonderful results – to focus on his gnarly face and hands as he talked about his garden’s various apple trees and their fruit.

-

On Rod Whitworth’s ‘Mr Knowles’

‘Happiness writes white,’ said Larkin, abbreviating Henry de Montherlant’s maxim, ‘Le bonheur écrit à l’encre blanche sur des pages blanches’ [‘Happiness writes in white ink on white pages’], but there are exceptions to all generalisations. The end of 2023 saw the publication, by Vole Books, of My Family and Other Birds, Rod Whitworth’s long-overdue first collection, full of poems which largely, though not exclusively, celebrate life and its myriad joys. Hats off to Janice and Dónall Dempsey at Vole for recognising that it needed to be out in the world. It’s available from them, here, or from Rod, here.

Rod asked me to write one of the two endorsements for the collection, which I very gladly did, but here’s a sentence from the other one, by Peter Sansom, which truly nails the book’s qualities: ‘The work of a skilful but unshowy writer, it is imaginative, open, honest and shrewd, and many other things besides, like funny and angry and loving – a chronicle in fully realised individual poems of lives and times.’Rod has kindly given me permission to quote the whole of the following poem.

*

Mr Knowles

Nine, in the sun, belly down

between cowpats and buttercups,

watching council houses

growing across the clough,

dreams held by the swing of the sledge

driving piles; I noticed

the thump at the top of the swept

arc, and was astonished.

But you knew, showed me how to count

the distance to the storm, see

the slip-catch held before the snick,

the shunting bounce before the bang.

You taught me nature has its laws:

how each effect follows from a cause.

*

This is evidently a poem about the power of knowledge and how it’s acquired and passed on; but it’s also more than that, of course, given the ground it covers in its 14 short-ish lines. It’s an informal sonnet, with the first two quatrains following an ABAB slant-rhyme pattern, the third unrhymed, and the closing, full-rhymed couplet neatly snapping the poem shut.

The opening stanza succinctly divulges a plethora of information in its 17 words, telling us the poet–persona’s age, the weather, likely time of year, location (presumably in Ashton-under-Lyne) and period (early-Fifties). There’s something very heartwarming about that ‘belly down / between cowpats and buttercups’; the unhurried, grass-level view of the post-war social-housing boom making Manchester greater. The scale and pace of building social housing fit to last then were phenomenal compared to today. That ‘growing’ is the word used and not ‘grow’ gives a better sense of time passing as the boy idly watches the housebuilding. The cross-Pennine dialect word ‘clough’, meaning a steep ravine, adds a lovely local specificity.

The syntax of the sentence which rolls across the first two stanzas is unusual because its subject doesn’t appear until halfway through the sixth line. It’s an effective device for front-loading the poem with lots of contextual facts . I daresay there’s a linguistic term for it. The phrase ‘dreams held by’ is a little ambiguous, though I presume it means something like ‘daydreams put on hold during’. (Could it have a secondary meaning too: that the sledgehammer’s swing somehow encapsulates dreams and ambition? Perhaps not.) I can’t remember ever seeing or hearing ‘sledgehammer’ shortened to ‘sledge’ before, but it works well here, not only because of the rhyme with ‘swept’: it enables the line to consist entirely of words of only one syllable, giving it almost a concrete sense of the repetition of the hammer’s blows. Then ‘driving piles’ is a satisfying phrase, enhanced by the deferred aural, and visually-mirroring, alliteration with ‘dreams’. The use of a semicolon here, rather than a comma, provides a slightly longer pause, as if the boy’s noticing is more active than his maybe more passive previous spectating. The third line (and into the beginning of the fourth) is also monosyllabic, and contains a delightful rhythm and music, thanks to those regular ‘p’ sounds. It takes a brave poet to include a clause like ‘and was astonished’ without it appearing grandiloquent and thereby unintentionally amusing to the reader; it succeeds here because it conveys the poem’s – and demands the reader’s – first emotional reaction, and, moreover, because the poet has wisely not spelled out the reason for the astonishment in big letters and has instead insisted that the reader do some work.

The introduction of the poem’s eponymous hero only at this point is nearly as late as that of Harry Lime in the film of The Third Man; that he appears without any description, even to tell us whether he is the boy’s schoolteacher or a local wise man, and that, crucially, he is directly addressed, beautifully shifts the register and augments the poignancy of the recollection. The whole of the third quatrain is especially wonderful, with its three further examples of actions preceding the sounds which they cause. The first is the most obvious, but is well-phrased and served by the smart line-break after ‘count’. The second is less universal since not everyone likes cricket as much as I do, but is fine nonetheless, with the italicisation of ‘snick’ reminding us of the word’s onomatopoeia. The ‘held’ here is either a deliberate echo of the same word in the second stanza or an oversight, but ‘taken’ wouldn’t have done the trick as nicely and putting ‘snatched’ between ‘catch’ and ‘snick’ would probably have over-egged the pudding. The third is a bit like a clown-car, with a cartoonish noise at its end, but could be far more serious.

The closing couplet is summative, yet isn’t clunkily so because it draws a wider conclusion and lesson than simply that happenings are generally perceived to occur prior to the sounds they create. Remembering that actions have consequences, we infer, has broadly influenced the decisions the poet has made throughout his life.

The poem leaves the reader to imagine what Mr Knowles looked and sounded like, the implication being that, like all the best teachers – in school, college, university or the university of life – he was a kind and patient man who imparted his erudition without fanfare. That description could also apply to Rod Whitworth and his poems.

-

On Michael Hamburger’s ‘In Suffolk’ sequence

Fine though the ‘Travelling’ sequence in Variations is, it is the second half of the book, the ‘In Suffolk’ sequence, which is its true heart. From the start of section I, the reader can sense his relief at being in what would become his permanent, final home:

So many moods of light, sky,

Such a flux of cloud shapes,

Cloud colours blending, blurring,

And the winds to be learnt by heart:

So much movement to make a staying.

The mood is lyrical and light, yet each line contains unforced enlightenment.

In section III he writes about the North Sea coastline, a few miles east of his house in Middleton, taking delight in what he perceives and in the names of other creatures, and giving free, breathtaking rein to the quirky syntax as one for whom English was not his mother tongue:

And what such jetsam tells

A man of the sea’s kinds:

Whelk spawn cluster,

Cuttlebone, kelp,

Jellyfish of the sea’s

Own and oldest making—

Made, unmade, still.

Not yet, though, or ever

one landscape, seascape, skyscape

But flux, only flux

To be learnt again and again,

Looked for, approved, accepted

Against the moment when seeing

Ends, because eyes have turned

Inward, fixed on a light

Less mutable, stiller, like that

In cornelian, agate, amber

Washed up on a shore, after winter tides,

And blindly the mind makes maps.

There is a beautiful, intrinsic humility to this poetry; and a deep recognition that the natural world has more to teach us about our place within this world than we can ever learn in our lifetimes.

-

On Michael Hamburger’s centenary

2024 – 22 March to be precise – marks the centenary of the birth of Michael Hamburger. He seems, sadly, to be more remembered these days rather more for his translations of and associations with great German writers than for his own poetry and criticism. That sense was reinforced by the first publication in English, in 2002, of W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn, chapter XII of which features a visit which Sebald’s narrator pays on Hamburger at his house in Middleton, Suffolk; Tacita Dean’s subsequent, extraordinarily beautiful film (2007; details available here) on Hamburger commissioned as a response to Sebald’s writing for the wonderful Waterlog exhibition; and the fact that Hamburger had translated two of Sebald’s poetry collections. (I wrote here, six years ago, about some of the connections between Hamburger and Sebald.)

To mark Hamburger’s centenary, this year I will periodically write about some of his writings, chiefly from the last third of his life when his poems, especially his nature poems, took on what I slightly hesitate to call a mystical quality. He’d never been a flashy poet, but, having taught at many universities in England and the USA, he was acquainted with poets of many different schools and styles, and his approach in his later years produced a more direct, informally formal poetry in which his thoughts were clearer and more powerful and affecting for being so. His late poems for me, are inspirational, as I hope I will show.

In 1981 (when Hamburger was the same age as I am now), Carcanet published his marvellous collection Variations which consisted of two sequences, ‘Travelling’ and ‘In Suffolk’, the second of which is particularly fine. Below, though, is a short, dizzying extract from part VIII (of IX) of ‘Travelling’, describing his weariness at the restlessness of moving by flight between positions and places elsewhere.

Estranged. By those global routes,

All curved now, all leading back

Not to the starting-point

But through it, beyond it, out again,

Back again, out. As the globe rotates

So does the traveller, giddy with turning, turning

And no return but for more departure,

No departure that’s not a return.

To what? To a home beyond home,

Beyond difference, indifference, sameness;

Beyond himself, who is here and there,

Who is nowhere, everywhere, in a season endlessly turning.

-

Poem in The North #69 – ‘The Blue Bridge’

In the last issue of The North, jampacked as ever with terrific poems and features, my poem ‘The Blue Bridge’ was included but got slightly mangled in the typesetting process, so I’m putting it here.

*

The Blue BridgeA truss bridge, to be technical;

in Knight’s Park, the sauciest

part of Kingston, at its patchwork

confluence with Surbiton.The chords of either arch

present a tempting post-pub dare:

inches narrow;

double-decker height

above the chalkstream shallows

of the Hogsmill’s grunt

towards Old Father Thames’s

indifferent embrace.My friend Paloma insists on this:

that after the Sham 69 gig’s

brutal aggro,

she watched her boiler-suited

Kinetic Sculpture lecturer

pigeon-step halfway,

stumble–tumbleand land midriver

on the platform heels

of his steel-toecap boots.

-

On Sarah Maguire’s ‘From Dublin to Ramallah’ and Ghassan Zaqtan

I’ve written before, here, about the debt I owe to Sarah Maguire, for the inspiration her poetry gave me to pick up my own pencil again. Moreover, she remains one of my favourite poets – possibly my very favourite contemporary poet despite the curtailing of her career by her tragic early death. Her lyrical, economical style was suited perfectly to her big themes: her adoption; London life; gender inequality; sex; flowers, gardening and, by extension, ecological catastrophe; migration; and the injustices suffered by the Palestinians and other peoples across the Arab lands.

The Pomegranates of Kandahar, her final (Chatto & Windus, 2007) collection, contained all those themes and more, with, as its title implies, a larger focus on the last of them. If any one poem in the collection stands out it is ‘From Dublin to Ramallah’, dedicated and directly addressed to the Palestinian poet and novelist, Ghassan Zaqtan, a small selection of whose poems, translated into English by Fady Joudah, is available here. The first of the 15 rolling, irregular quatrains in Maguire’s poem opens with the message that she is writing a (poetic) postcard to him because he had been denied a visa to travel to Ireland, presumably to attend the Dublin Book Festival:

Because they would not let you ford the River Jordan

and travel here to Dublin, I stop this postcard in its tracks –

before it reaches your sealed-up letterbox, before yet another checkpoint,

before the next interrogation even begins.

What purpose does the anaphora of ‘before’ serve here? Primarily to underline the oppression suffered by Zaqtan and his compatriots, but also to reinforce the comparative liberty which we in the UK, Ireland and other countries take for granted?

That Maguire is writing from Ireland – and from ‘the underwater backroom / of Bewley’s Oriental Café’ on Grafton Street at that – has two other significances: that it is the home country of her adoptive and blood relatives; and because of an unstated historical parallel between the situation of the Irish and Palestinian peoples, both subject to violent subjugation and colonisation.

The Orientalist setting of Bewley’s and its Far- and faux Middle-Eastern fare, provides another curious parallel of sorts, carefully and precisely observed by Maguire:

I ship you the smoked astringency of Formosa Lapsang Souchong

and a bun with a tunnel of sweet almond paste

set out on a chipped pink marble-topped table

from the berth of a high-backed red-plush settle.

The delicate, yet pointed beauty of that ‘smoked astringency’ is remarkable: ‘smoked’ with its connotation, maybe, of burnings-out; and ‘astringency’ with its multiple meanings, including bitterness, and curious etymology; and its apparent conflation of ‘stringent agency’ – an agency stringent in its suppression of individual and collective freedoms. The choice of a tea from Formosa, i.e. Taiwan, an island nation under perpetual threat of invasion by its much more powerful neighbour can’t be coincidental.

Outside the Liffey and the city itself are being inundated, such that ‘the cream double-decker buses steam up and stink // of wet coats and wet shopping’. From here, the complexity of Maguire’s concerns, ‘Closer to home and to exile’, become further entwined with Zaqtan’s plight, by blurring geographies in language which feels far from typically English:

I ask for a liquid dissolution:

let borders dissolve, let words dissolve,

let English absorb the fluency of Arabic, with ease,

let us speak in wet tongues.

Look, the Liffey is full of itself. So I post it

to Ramallah, to meet up with the Jordan,

as the Irish Sea swells into the Mediterranean,

letting the Liffey

dive down beneath bedrock

swelling the limestone aquifer from Hebron to Jenin,

plumping each cool porous cell with good Irish rain.

If you answer the phone, the sea at Killiney

will sound throughout Palestine.

If you put your head out the window (avoiding the snipers please)

a cloud will rain rain from the Liffey

and drench all Ramallah, drowning the curfew.

There is a measured but desperate urgency here, enhanced by the rolling rhythm, repetitions, musicality (all those ‘l’s) and acute line-breaks.

In Beyond the Lyric (Chatto & Windus, 2012), her brilliant, though at times (understandably) eccentric ‘map of contemporary British poetry’, Fiona Sampson a little bafflingly lumped Maguire with Gillian Clarke and Michael Longley as what she called ‘touchstone lyricists’. Sampson perceptively noted, on page 87, that this poem,

is almost cavalier in it refusal to sound ‘crafted’: ‘rain rain’? Could Maguire really find no synonym for this kind of weather? Of course she could. The micro-pause that the repetition introduces allows us to glimpse the ghost of a half-line break, which moves throughout this poem – a trace of the parallelism of some Arabic verse. The pattern is broken only by that disobedient ‘throughout’ unfolding its long vowels in a deft piece of mimesis.

It’s a pity, perhaps, that Sampson didn’t pursue that ‘trace’. And her last observation seems a bit of a stretch – no pun intended – to my eyes and ears – I get what she means; albeit that there is so much to the poem which Sampson could have glossed.

Zaqtan, still in Ramallah, in the West Bank, remains on X/Twitter, here; his latest post, yesterday, loosely translates as:

I was born in the homes of Christians in Beit Jala

In the stone houses above the olive presses

Where heavy stones roll in the fall

Where Arab women draw the sign of the cross whenever oil flows into the gutter

Born among women

In the course of hymns, when Sunday had the smell of tea and mint

On the balconies of Muslim women.

-

Some of my favourite poetry books of the year

What follows is a canter through a baker’s dozen of poetry books I read and enjoyed this year that I haven’t already written about on this blog or reviewed elsewhere (including one for which my review is due to appear in 2024).

My best present last Christmas was Jane Kenyon’s Collected Poems (Graywolf Press), which occupied a good deal of my poetry head for a few months at this year’s outset. Her poems are so much more than just her celebrated ‘Let Evening Come’. Re-opening the book at random, I find ‘Year Day’ and its extraordinary opening stanza, with enough going on to keep my mind busy for ages before advancing any further:

We are living together on the earth.

The clock’s heart

beats in its wooden chest.

The cats follow the sun through the house.

We lie down together at night.Having previously read and loved a couple of Jane Hirshfield’s collections, it was high time I read more of her poems, so I got her selected poems, Each Happiness Ringed by Lions (Carcanet), which, despite being annoyingly ordered in reverse chronology, has almost as much treasure within as the Kenyon book.

Sarah Wimbush’s Shelling Peas with my Grandmother in the Giorgiolands occupies much of the same cultural space as Jo Clement’s Outlandish (both published by Bloodaxe): Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities in the north of England. Wimbush’s greater formal variety made it for me the marginally more compelling read, but it’s not a competition and they are both rich, important collections.

Paul Stephenson’s Hard Drive (Carcanet) saw him bring to bear all his repertoire of poetic skills upon grief at the loss of his partner. I can’t think of another contemporary poet who deploys such a large variety of forms to such devastatingly fine effect. It’s a big, unmissable collection.

Luke Samuel Yates is another playful poet, who spins language with an artfulness which is both inherited and very much his own, and his first collection, Dynamo, was, like Stephenson’s, long overdue but well worth the wait. Like his dad, Yates has the driest wit but always with an underlying serious look at life, as befitting a professional sociologist – as demonstrated by a post-Dynamo poem here.

The 19 poems in Josephine Corcoran’s Live Canon pamphlet, Love and Stones, are all big ones, addressing meaty themes, not least the tricks of time and the joys of, and worries about, family and nature. Take, for example, the opening stanza of ‘Parenting book’:

I wrote it down when you woke me at 3am

to tell me you didn’t like ham anymore.

Only jam. And cheese. How the shower cubicle

was where a murderer would lurk.

Appearing a whopping 19 years after his debut collection, Matthew Hollis’s second, Earth House (Bloodaxe), is chock-full of his majestic, measured poems in which time and place are delicately explored. Carol Rumens discussed one as ‘Poem of the Week’ in the Guardian, here.

Vanessa Lampert’s Say It with Me (Seren) contains a lifetime of wit and wonder, as profound in dealing with the minutiae of life as with all the heavy stuff.

Tiffany Atkinson’s fourth collection, Lumen (Bloodaxe) is a book of two halves: 19 poems she wrote on a residency in a hospital in Aberystwyth and a miscellaneous mash-up including a wonderful prose-poem sequence, ‘You Can’t Go There’. I especially loved ‘The Smokers Outside Bronglais Hospital’ in which,

The nurse in her peppermint uniform

throws them a sneeze and her ponytail swings

I’d never read John Birtwistle before his Partial Shade: New & Selected Poems (Carcanet) appeared, but I very much enjoyed his subtle, quite observational style. In ‘On a Pebbly Beach’, he writes,

it struck me that grownups tend to select

those that the sea had spent her centuries of energy

smoothing and buffing

from rock until perfectly formal, the ovoid, the oval

but our youngsters go for the grotesque,

the knobbly ones with fractured faces and funny holes

that can have fingers poked in and out of them

or look like puppies or gulls

Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana’s Sing Me Down from the Dark (Salt) recounts memories of a decade of living and loving in Japan, and its aftermath back in England; a warm, honest collection of skilfully crafted poems.

Lastly, the unshowy, but deeply beautiful poetry in Marion McCready’s third collection, Look to the Crocus (Shoestring), is as fine as anything I’ve read in 2023, and would win awards in the parallel world where justice prevails. As the title implies, one of McCready’s concerns is flowers, and I would go so far as saying that she writes as well about them as the late great Sarah Maguire did. Here is the start of ‘Pink Rhododendrons’, with similes as arresting as Plath’s or Thomas James’s:

They are opening toward me

like a gang of babies, or puppies,

or wedding bouquets;

creatures from another world.

But McCready writes equally well about family and place, most notably perhaps, in the magnificent ‘Ballad of the Clyde’s Water’, which first appeared in Poetry (Chicago). It’s an absolute corker of a book.