You might think it invidious at the moment to be reading books by anyone called Donald, so it’s strangely coincidental that I’ve just read two in a row. I’ve mentioned before that Lyn and I have read several books recommended by the excellent Jacqui’s Wine Journal website, and Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper by Donald Henderson is the latest of them. Jacqui reviewed it here, and her verdict is as dependably spot-on as ever. It’s very much a period piece as many older crime novels are, but that’s its joy.

Toy Fights, Faber 2023, Don Paterson’s memoir of the first 20 years of his life, is full of the rich details and meta-commentary that readers of his poetry would expect. His recall of memories is phenomenal, as if he’s channelling Ray Bradbury, who said, on Wogan in the Eighties, that he could remember everything that had happened in his life, even back into the womb. Paterson says, though, that, after three years of age,

the memories are vivid, but they still can’t be trusted. I am wont to confuse memory and photographs, other folks’ memories with my own, and things I saw on television with things that happened to me.

Paterson writes well about his jobbing musician father, at whose club gigs Paterson joined him as a side guitarist from the age of 15, though his mother, still alive at the time the book was written, is less of a presence. The biggest character, aside from Paterson himself, is the city of his birth and upbringing, Dundee. As a fan of the joyously daft BBC4 sitcom Bob Servant – written by Neil Forsyth who also wrote the fantastically well-plotted The Gold among other things – I was pre-programmed to like the colourful characters, community spirit and language of Dundee which Paterson brilliantly and often hilariously conjures. He’s very good, too, about the painful years of his adolescence, including two or so years as a devout Christian in a cult-like group, and his subsequent musical education, as listener, player and part of the local music scene, which at that time encompassed The Associates, led by much-missed Billy Mackenzie. The most memorable section concerns a breakdown he had aged 19, chiefly caused by drugs, and his subsequent four-month stay in Ninewells (psychiatric) Hospital. The book ends with Paterson setting off for a job in a band in London. Poetry barely gets a mention. Paterson’s ability to self-analyse with candour and honesty is extraordinary and provides many of the book’s funniest moments.

I’ve written before, here and here, of my admiration for the writing and performing of Philip Hoare, and it was about time that I got stuck into his book Spike Island (Fourth Estate, 2001), subtitled ‘The Memory of a Military Hospital’. Ostensibly, it’s concerned with the history of the humungous hospital built from 1856, opened in 1863 and mostly demolished in 1966, at Netley, near Southampton; but it’s much more than that, suffused as it is with Hoare’s memories of growing up a stone’s throw away in Sholing, his family history in general, aspects of British social history from mid-Victorian times and much else. It’s the most Sebaldian of his books, I think, with photographs interspersed throughout, and was in fact one of the last books which Sebald himself endorsed, in the Sunday Telegraph books of the year, before his death in December 2001: ‘A book that has everything a passionate reader could want – a subject that far transcends the trivial pursuits of contemporary writing, concerns both public and private, astonishing details, stylistic precision, a unique sense of time and place, and a great depth of vision.’ Hardly unique, though, as those words could’ve been applied to any of Sebald’s own books. Thanks to its proximity to the port of Southampton where the troopships docked, all British soldiers injured in the nation’s colonial wars were initially treated there, including those suffering from shell-shock inflicted on the Western Front, who were sectioned off in ‘D Block’, where the dreadful treatment was very much based on the notion of using military discipline to bully the inmates back to some kind of ‘normality’. I thought of James Goose, my great-grandfather, who was sent to South Africa in 1899 as part of a Norfolk militia regiment, got shot in the face by a Boer sniper (the wound turned cancerous and killed him years later) and came home on a ship named Roslin Castle, pictured here: he was so relieved to be home that he and my great-grandmother Agnes (née Riches) named their son Roslin, though maybe sensibly he was known as Rossie.

On the poetry front, I much admired Richard Scott’s second collection, That Broke into Shining Crystals, Faber, published earlier this year. As in several of Pascale Petit’s collections, this contains work which very skilfully, and with a marvellous ear for musical cadence , transforms the pain of sexual abuse into beautiful poetry. Each of the 21 poems in the first section, Still Lifes, responds to a different still life painting by painters from the 1600s onwards to Bonnard. The second part, a response to Marvell’s ‘To his Coy Mistress’ felt less successful, as it employs Seventeenth Century language in a manner verging on parody. The third section contains 22 poems after types of crystals and gemstones, as refracted through Rimbaud’s Illuminations as translated by Wyatt Mason, and are, for me, the most successful in the book, because the prose-poem form allows Scott to give fuller vent to his gift for articulating emotion through vivid and sensuous imagery and language, as in this extract from ‘Emerald’:

The field is a body. Wild grass rippling over breasts and muscles, the jut of a hipbone. Some of the grass is trampled down into mud like a battlefield – screams catch the air. Some of the grass is spread over little hillocks like shallow graves. Some of the grass is cut into a bit, desire lines and goat paths, leading to all the places you ever dreamed of going but didn’t.

As I discovered from listening to his interview with Peter Kenny in Series 5, Episode 10 of the ever-excellent Planet Poetry podcast, here, Scott talks very thoughtfully and eloquently about his craft.

I’ve also been knee-deep in the poems of Wisława Szymborska, as translated by Clare Cavanagh and collected in Map, Houghton Miflin Harcourt, 2015, for the poetry book club I’m part of. My jury is still out thus far, but then it’s a heftily daunting tome.

I’m also about halfway through Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry, published last year in the USA by Graywolf and in the UK by Fitzcarraldo Editions. Her telling-it-as-it-is style might not be everyone’s cup of tea, but I really like the way she throws it all in and takes disjunctive leaps in her poems. I adore her poem ‘An Aria’, 23 irregular quatrains which are propelled with a fearsome energy. I found myself getting funny looks on the Tram Train to Sheffield last Thursday as I read out sotto voce. If poetry can make me do that, it has to be good.

-

July reading

-

On revising poems

How many times have I tinkered with a poem before realising that I’ve overcooked it, so then had to undo the change? It’s a good job I’m not a builder. Sure, no one wants to read the obvious word every time, but poets can of course overdo the tweaking by replacing the early-draft choices with alternatives whose other connotations are so far from being synonymous that they blur the original meaning and/or unbalance the syntax to an unbearable degree.

In his Paris Review interview with Frederick Seidel, Robert Lowell said this:

You think three times before you put a word down, and ten times about taking it out. And that’s related to boldness; if you put words down, they must do something, you’re not going to put clichés.

And this:

Almost the whole problem of writing poetry is to bring it back to what you really feel, and that takes an awful lot of maneuvring.

By that, I infer that he means how the emotional kernel of the poem is conveyed and encased by the rest of it. The best advice I ever received from another poet was to ensure that every poem, like the Tin Man, had a heart.

When Seidel asked him if he revised a great deal, Lowell’s answer was emphatic: ‘Endlessly.’

Time is the poet’s greatest ally in revision: each and every poem needs to be set aside for a long enough period before the poet comes back to it and decides whether or not it needs more work. If there is a niggle at the back of your mind that some aspect of the poem isn’t quite right, then you can bet that an editor would spot it straight away, so that niggle can’t just be ignored before the poem is released into the wild.

But I’m as guilty as anyone of having, many times, sent off in a bout of unfounded enthusiasm a recently- or even just-written poem which hasn’t been allowed to settle into its best form. Wherever you are, I expect you could hear my sighing earlier today while I spent three hours rejigging a poem, which, thinking it was well and truly finished, I submitted to a journal only last week.

All of which begs the question as to when a poem is actually finished, if at all. In my case, it certainly wouldn’t, by any means, be finished if it were published in a journal or in a pamphlet, although I would do my level best to try and resist tinkering with it before including it in a full collection. Even then, perhaps only the reader can complete it, though that cliché sounds as trite as any other cliché.

-

On Rod Whitworth again

I’ve written about Rod Whitworth on this blog before, here. Rod is a very fine poet and one of my fellow members of the fortnightly workshopping group, the Collective.

Rod has four outstanding poems in the latest issue – #97 – of the ever excellent Pennine Platform, which is one of my very favourite poetry journals, and I’m very pleased to see that over on the journal’s website, you can now have the treat of hearing Rod reading one of them, the beautifully tender ‘Still Growing’, and see a lovely artwork by Rod’s wife, Ange. The poem and image are here.

-

Another review of The Last Corinthians

I was thrilled this morning to discover that the excellent novelist and poet Ali Thurm has reviewed my book over on her always highly readable Substack, here.

It was very gratifying to see the care and attention with which Ali had read and written about my book, and to know that she gets what my poems are about.

I can highly recommend not just Ali’s Substack but also her gripping novel, One Scheme of Happiness, published by Retreat West Books. Ali has another novel due out later this year, from Valley Press’s Lendal Press imprint, so I’m looking forward to that. You can read more about Ali and her writing here.

-

Review of Anna Woodford’s Everything is Present

With thanks, as ever, to Hilary Menos and Andy Brodie at The Friday Poem, my review of Anna Woodford’s third poetry collection has been published today, here.

-

Reviews of The Last Corinthians

As a fairly frequent reviewer, I know how much thought and effort goes into attempting to produce a fair summary and consideration of a poetry publication. The reviewer has to be mindful that poetry books and pamphlets, whatever their quality may be, are, of course, the result of at least several years of writing, revising and constant striving for improvement – and debuts have a lifetime behind them.

For me, though, it’s marginally more nerve-wracking to be the reviewee than the reviewer. Twice in the last fortnight, I’ve been fortunate to read reviews of my new collection, and I’m very grateful to the editors of The High Window and The Friday Poem – David Cooke and Hilary Menos, respectively – for commissioning and publishing them. I say fortunate because some poetry collections receive no reviews at all, and others garner them belatedly, as I experienced: my first collection was out in the world for over a year before its first review appeared.

I’m even more grateful to Rowena Somerville and Jane Routh for taking the time and trouble to read my poems closely and attentively and then to write about them and how they cohere.

Rowena Somerville’s review can be read here.

Jane Routh’s review, plus a poem from the book, ‘Old Man of the Woods’, can be read here.

-

Poems in Black Nore Review – ‘Twelfth Man’ and ‘Staycation’

With thanks, as ever, to editor Ben Banyard, I have two new poems up at Black Nore Review today, here.

-

May and June reading

Due in large part to preparing for my book launch events, my reading became much less systematic in the last two months, which is probably no bad thing.

I read four of Henning Mankell’s Wallander novels back-to-back: The White Lioness, The Man Who Smiled, Sidetracked, The Fifth Woman, respectively the third, fourth, fifth and sixth in the series. Having watched the BBC Kenneth Branagh adaptations several times, over the years and the Swedish one also, it’s very interesting to see how much television omitted, presumably to increase the pace. I prefer the books, with the intricate, methodical unfolding of the plots and the laying bare of Wallander’s desultory lifestyle beyond his policing. Well ahead of his time, Mankell put geopolitical inequalities at the heart of his books. I admire his offbeat, serious wit, too, such as this, from The Fifth Woman:

Linda poured herself some tea and suddenly asked him why it was so difficult to live in Sweden.

“Sometimes I think it’s because we’ve stopped darning our socks,” Wallander said.

She gave him a perplexed look.

I was very late to A Crime in the Neighborhood by Suzanne Berne, first published in the UK by Penguin in 1998 and winner of the Orange Prize for Fiction in 1999. It’s a beautifully written novel written in the voice of Marsha, a nine-year-old girl living with her mother and teenage twin siblings in Washington D.C. at the time of Watergate. Her father has left the home to be with her mother’s youngest sister. Against that backdrop a terrible crime happens, but this isn’t a crime novel, but one which memorably depicts Marsha’s thoughts and actions, and their consequences, and how a family unravels.

I can’t remember the last time I read and enjoyed a book of short stories as much as I did Jonathan Taylor’s Scablands and Other Stories, published a few months ago by Salt and available here. Its 20 stories aren’t long – they range in length from one page to 33 pages – but Taylor is highly adept at squeezing maximum value from his prose. Even in stories which ostensibly entail time-travelling, the tales and characters are believable, as are the varied narrative voices. My favourites were ‘Heat Death’, involving the whereabouts of a lottery ticket, and the title-story, about a bullied pupil and a teacher at the end of his career, but they all earn their place. These are contemporary stories, unafraid to explore the impact of deprivation and other complex social situations. I’m very glad that it won this year’s Arnold Bennett Prize – our household contains more fiction by Bennett than any other writer.

On the poetry front, I’ve been reading a couple of books for reviewing, plus others. I bought – again belatedly – a copy of Julia Copus’s most recent (2019) collection, Girlhood, as I always like her poetry. The first poem ‘The Grievers’, available here, is an absolute belter, which beautifully conveys how grief shape-shifts. I love these lines: ‘We steady our own like an egg in the dip of a spoon, / as far as the dark of the hallway, the closing door.’ This and the other 11 poems – including a trademark specular (the form Copus invented) – which constitute the book’s first section are all excellent, showcasing her knack for choosing surprising, just-so words and for making sharp, but not daft, line-breaks. The book’s second and larger section inventively dramatises the interactions between Jacques Lacan, the psychoanalyst and philosopher, and Marguerite Pantaine, perhaps his most famous case study. It’s a sequence which needs to be read at least twice, I think, to yield its treasures. It hints at the possibility of Copus, having also written a biography of Charlotte Mew, writing a novel. Coincidentally no doubt, the last poem in the sequence, ‘How to Eat an Ortolan’ is remarkably close in tone as well as content to Pascale Petit’s ‘Ortolan’ in Fauverie, her brilliant 2014 Seren collection (my favourite of her first eight collections – I haven’t read the new one yet). Compare:[. . .] He bends to the dish,

hears the juices sizzle and subside,

then picks the bird up whole by its crisp-skinned skull,

burning his fingers, and is stirred for a moment

by its frailty (it is light as a box of matches);

places it into his mouth, but does not chew.

[. . .]

(Copus)[. . .] Eight minutes he waits

while the bunting roasts, then it’s rushed sizzling

to his lips, a white napkin draped over his head

to envelop him in vapours – the whole singer

in his mouth, every hot note. The crispy fat melts,

the bones are crunchy as hazelnuts. When

the bitter organs burst on his tongue in a bouquet

of ambrosia he can taste his entire life [. . .]

(Petit)

Even as a vegan, I can appreciate the extravagant verbal dexterity of both poems.

-

Post by Mat Riches

My friend and fellow poet, Mat Riches, has very kindly written a blog piece on my poem ‘Fire Evacuation Procedure’, here.

Mat did me the honour of reading, beautifully, last Tuesday evening at the London launch of my new book.

As you may already know, Mat’s blog is always interesting, but if you haven’t already had a look at it, then his back catalogue is very much worth losing a few hours (or more) in.

-

Readings in London on Tuesday, 17th June

The third event to launch my new collection, The Last Corinthians, will take place this coming Tuesday evening at The Devereux pub, 20 Devereux Ct, Temple, London, WC2R 3JJ. It’s a free event so if you’d like to be there, just come along – you’ll be very welcome. Readings will start at 7.30, in the function room upstairs.

As above, alongside me, there will be readings from a trio of outstanding poets: Mat Riches, Ian Parks and Vanessa Lampert. All three of them have been very supportive of me and my poetry, but, more importantly, they’re also fabulous readers of their own poems.

-

Launches

This coming Tuesday evening, at 7.00 BST, will see the online launch of The Last Corinthians, where I will be joined by two fabulous guest readers, Shash Trevett and Cliff Yates. If you would like to come along, places are free but please register at the Crooked Spire Press website, here.

*

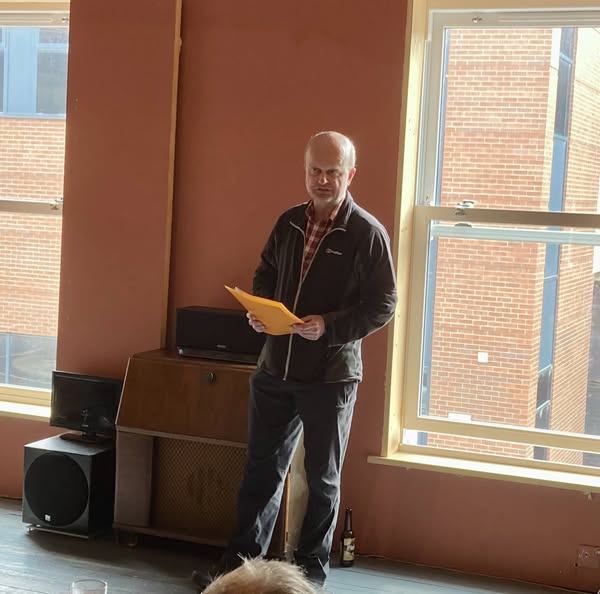

Yesterday saw the first launch event for the book, at Doncaster Brewery Tap. It went as swimmingly as I could possibly have hoped for. My thanks to Alison Blaylock at the Tap, Tim Fellows of Crooked Spire Press who made the book happen, to a lovely and enthusiastic audience and to my two guest readers, Ed Reiss and Victoria Gatehouse, who both read beautifully. Greg Freeman has very kindly written an account of the event on the Write Out Loud website, here.

Me reading, photo by Liam Wilkinson

Ed Reiss reading

Victoria Gatehouse reading

-

On The Last Corinthians

It’s taken 10 years and a whole lifetime to bring my new collection to fruition. As with my previous books, there have been false starts and a great many changes as this one has evolved. I’ve needed the help of feedback on drafts of poems – by Red Door Poets, an in-person workshopping group, of whom I was a member from its founding until 2020; South Ken. Stanza, a fortnightly email workshopping group; and, above all, the Collective, a fortnightly Zoom group, whose comments and support have been invaluable. But then again, writing poems is almost always a solitary activity, so first and foremost I’ve had to trust my instincts and have faith in whatever ability I have. By the end of collating the collection, 56 of its 62 poems had been previously published in journals.

Back cover of The Last Corinthians As a fairly regular reviewer of collections, I’ve often read books which don’t have an overtly coherent sense of what the poet is trying to say, other than within individual poems. That’s not to say that there’s anything intrinsically wrong with that, but most poets write poems which speak to, or echo, one another – either directly or indirectly – thus it seems appropriate to make that at least partially explicit through the poems’ ordering. In my case, I gradually took care to carve my manuscript into thematic sections. The drawback with that was that some previously published poems which I think are still not bad didn’t make the cut, because I couldn’t make them fit with the collection’s overall arc.

I was also at pains, as I was with my first collection, to ensure that there were notes at the back. I know that many poets prefer not to do this, in the spirit of ‘never explain’; I, though, don’t see notes as being explanatory but, rather, as helpful to the reader: as a White English, middle-aged male, I can’t expect every reader either to know or understand, at first glance, all of my cultural references; neither do I expect them to look them up online (or even in an encyclopædia!). Assembling notes at the back of the book seems to me to be a sensible thing. There is, of course, a fine balance to be struck between stating who a particular person, painting, TV programme or whatever is, or was, and (in my case) mansplaining in a manner which tells the reader what the poem is about – I like to think that my book, its three sections and the individual poems by and large speak for themselves. I’m not the kind of person who likes to write, or read, cryptic poems. Again, though, I would add the disclaimer that neither would I want to write poems which could be so easily understood at face value that they had no resonance.

As an inveterate tinkerer with poems, some – perhaps as many as half of them – took at least a year, and in some cases more than five years, to be settled. You might therefore not be surprised to hear that the title of the book has also changed lots of times in the last decade. In fact, I only plumped for The Last Corinthians less than two months before the manuscript went to the printer. I should say here that I’m very glad that Crooked Spire Press used a local printer, because supporting the local economy sits squarely with the book’s values. I should also say how grateful I am to work with a publisher who ‘gets’ my poems and what I have tried to achieve with the book.

So why did I choose this title? Well, it derives from the title of the longest poem in the book. That poem was largely concerned with the now long-gone phenomenon of the footballer–cricketer, who excelled enough to play at the highest levels at both sports. Beyond that though, is a sense that the phrase the last Corinthians alludes to how England, Britain, the UK and beyond has changed, mostly for the better, during my, and my immediate antecedents’ lives. I don’t have the slightest hint of rose-tinted hankering for the past, in which imperialism and discrimination very openly thrived; yet, the world before the internet and social media naturally had some pluses as well as technological and societal limitations.

My parents’ generation were born during the desperately tough times of the 1930s, experienced the trauma of war on the home front, and came of age in the Fifties, a decade when rationing was still in force for half of it, opportunities for young women were still extremely limited and young men, including my father, were called up to do National Service, some of whom ended up fighting in Korea or against independence movements in Kenya and Cyprus. Others were even exposed to the fall-out of atomic bomb tests in Australian deserts. Class and other forms of social exclusion were endemic. Roy Jenkins’s and others’ work in the Labour governments of the Sixties and Seventies to improve society through legislation – the Race Relations Act, the decriminalisation of male homosexuality and of abortion, the Sex Discrimination Act, etc. – was crucial, as was further legislation, most notably the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 and the overarching Equality Act 2010.

As is obvious, though, improvement was, and is, wrought not just by the law, but much more so through changes or reinforcements of individual and collective behaviours and moral values. Despite the Farage riots last August, Reform’s recent local government successes, and many inequalities which our current government is yet to address (and in some instances has worsened, e.g. the assault on people with disabilities and support for Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians), and despite the influence of despots on the wider world stage, this country remains one in which the overwhelming majority of people seem to act in accordance with a sense of community and compassion for most of their time. Throughout my career in local government, I was motivated by a sense of moral purpose, of wanting to help to improve the lives of children, young people and their families.

So, I hope that readers of The Last Corinthians will be able to discern some or all of that in the poems and themes which it contains. On the back cover (photo above), it says, that the book, ‘veers psychedelically through history, pausing for quieter moments’ and my inkling of what ‘psychedelic’ means is a nostalgia, in the present, for a past which never quite existed in the way I remember it. Is it absurd to self-identify as a psychedelic poet? Answers on a postcard from the future, please.

-

On Pam Thompson’s ‘Edvard Munch in Haverfordwest’

It would be difficult not to like Pam Thompson’s poetry, because it has immediacy, depth and variety. Her Sub/urban Legends won the Paper Swans Press Poetry Pamphlet prize in 2023 and has recently been (rather belatedly) published. At only £5 (plus p&p) it’s a genuine bargain and is available to buy here. It’s Pam’s first publication since her excellent second collection, Strange Fashion, published by Pindrop Press in 2017.

In his adjudication of the Paper Swans prize, John McCullough wrote:

Sub/urban Legends gripped me because of the way it marries poignancy with a really bold imagination and stylistic flair. Its poems exploring both experiences of parenthood and mourning the loss of a maternal presence find a great balance of a lively eye and, where it’s most needed, a heartfelt clarity and directness.

Pam is influenced, inter alia, by the New York school of poetry, a loose amalgam of poets associated in the 1950s and ’60s, chief among them Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Barbara Guest, Kenneth Koch and James Schuyler. Pam has discussed her particular liking for, and the influence of, Schuyler in an intriguing 2023 podcast with Chris Jones, here. The deceptively offhand diction of the New York poets, their acute but apparently nonchalant awareness of what’s going on around them, their precision, urban sensibility and painterliness can all, I think, be discerned in Pam’s poems. And as she says in the podcast about the New York poets’ poems, hers are almost always ‘peopled’.

Sub/urban Legends doesn’t feel like a themed pamphlet, because it isn’t one. Its 24 poems are varied in tone, subject-matter and form, and each of them is worth spending time with.

Pam has kindly given me permission to quote the whole of the following poem.

*

Edvard Munch in Haverfordwest

Easter Saturday, his type of weather—

squally, grey. He wanders up the High Street,

buys a cagoule and a flask from the Army and Navy,

considers a Magilux torch but puts it back.

WHSmith are giving away Cadburys mini-eggs

with the Daily Mail. He queues for ages.

The man behind the till insists he must take

this newspaper and not the one he prefers.

Three young women with piercings in their faces

are leaning against the railing outside Tesco—

one has sea-green hair. When he paints her

he’ll make the colours vibrate until you can hear them.

He buys tomatoes and crusty bread.

As she fills the flask, the woman in Greggs

seems to understand what he says to her in Norwegian.

On St Mary’s Bridge he has some sort of turn

that history will repeat— on pub signs, posters,

as though all the portraits of his homeland,

of his sister on her sickbed, never happened,

but it passes and the world stays still again.

This morning, it’s all the time it takes to feed ducks

on the river and pour coffee from a blue enamel flask.

*

Munch, 1863–1944, brought an explicitly psychological edge to his paintings; not just, but most famously, in the several versions of The Scream which Pam’s poem alludes to in the eighth and ninth couplets. (I remember seeing all extant versions Munch made of it in an exhibition at the Barbican in 1985 and being surprised by how small they were.) He lived through times of immense change in Norway and beyond, and died 15 months before his country was liberated from the Nazis. Alas, his funeral and legacy were hijacked by Quisling and other Norwegian collaborators and by the occupying Nazis themselves.

Whether or not Munch ever went to Haverfordwest is irrelevant; the poem takes fundamental liberties in placing him there, and doing so in our time – liberties which the reader can happily go along with as Munch perambulates along the town’s streets. Why Haverfordwest? Well, why not? My maternal grandfather’s New Standard Encyclopædia and World Atlas from 1933 says of Haverfordwest that, ‘In the days when ships were small it was a prosperous port.’

It’s a poem rich in specificity from the outset: I guess technically Easter Saturday falls six days after Easter itself, though I suspect most of us think of it as the day between Good Friday and Easter. Either way, it places the poem firmly in springtime, on a fair-to-poor day, as the shorthand of ‘squally, grey’ tells us. That colloquial ‘his type of weather’ is a lovely and confidently omniscient narrative assertion. The verb choice is interesting too: that Munch ‘wanders’ rather than ‘hurries’ or one of its synonyms, implying that, being a Norwegian and therefore somewhat hardy vis-à-vis inclement weather, squalls are water off a duck’s back to him. Nonetheless, in the next couplet we see Munch buy ‘a cagoule and a flask’, as if the weather is actually more of a nuisance than it first appeared, to the point of needing proper outdoor clobber. That he does so in ‘the Army and Navy’ is wryly amusing. I don’t know if any Army and Navy stores are still open in Britain, but, again, that’s irrelevant, because it sounds just right. It’s amusing too, how Munch ‘considers a Magilux torch but puts it back’, presumably, the reader senses, because of the price, his implied thriftiness just another small detail which we accept as true thanks to the poem’s this-is-how-it-is descriptive tone.

The third and fourth couplets are also funny, in a droll manner, but what’s also admirable is how the third couplet’s opening is constructed: instead of saying something comparatively pedestrian (pun intended) like, ‘He enters WHSmith where they are giving away / Cadburys mini-eggs with the Daily Mail, and he queues for ages’, the clauses are cleverly compressed. We sense Munch’s boredom and impatience in that ‘for ages’, and then his frustration at not being able to transfer the deal from that right-wing rag to the Guardian or whatever. But of course, we are allowed to infer those feelings, due to the poet trusting her readers. Now that WH Smith has been bought over and its stores are disappearing from our high streets, its inclusion here was prophetically poignant. Pam is too good a poet not to choose the particular details in her poems with the utmost care and consideration as to their resonances.

The fifth and sixth couplets allude to, and crucially reinvent, Munch’s famous Girls on a Bridge, which he painted 12 versions of between 1886 and 1927. (Derek Mahon used the 1901 version for his marvellous six-strangely-shaped-stanzas poem of the same name, in which he described ‘Grave daughters / Of time’.) Here, again, there is further fine accretion of detail: the ‘piercings in their faces’, ‘the railing outside Tesco’ (compare Mahon’s ‘The girls content to gaze / At the unplumbed, reflective lake’) and that truly excellent ‘sea-green hair’, somehow perfectly appropriate, not just because Haverfordwest is/was an inland port but also because Munch, strongly influenced by van Gogh and Gauguin, was fond of using bold colours and because it shows another assertive streak of independence to these ‘young women’. This is, of course, a poem which time-travels – both physically and attitudinally. (Munch, it should be said, has been posthumously accused of both misogyny and feminism in how he depicted girls and women.)

At this point in the poem, just the right moment after the layering-on of precise visual details, the narrative commentator re-enters the poem with that beautifully synaesthetic sentence, with its hint of Magical Realism, ‘When he paints her / he’ll make the colours vibrate until you can hear them.’ Note that it’s ‘colours’, not ‘colour’: we are reminded that this is a painter whose palette dazzles.

For me, the thought comes that the first six couplets might work better, in terms of their discrete content, as quatrains:

Easter Saturday, his type of weather—

squally, grey. He wanders up the High Street,

buys a cagoule and a flask from the Army and Navy,

considers a Magilux torch but puts it back.

WHSmith are giving away Cadburys mini-eggs

with the Daily Mail. He queues for ages.

The man behind the till insists he must take

this newspaper and not the one he prefers.

Three young women with piercings in their faces

are leaning against the railing outside Tesco—

one has sea-green hair. When he paints her

he’ll make the colours vibrate until you can hear them.

However, one can intuit that the poet ruled that idea out for four reasons: that what immediately follows those 12 lines has, until the end of the penultimate couplet, an almost continuous syntax (despite the full stop midway through the eighth couplet) which better suits the couplets form; that, in any case, there are 11 couplets, rather than 10 or 12, and therefore they couldn’t all be arranged as quatrains; that the unfolding of the couplets also ideally suits the leisureliness of Munch’s morning walk (or ‘Morgenspaziergang’, per the title of a Kraftwerk track, on Autobahn); and one other reason which I’ll come to later.

But back to the content. After we readers momentarily dwell upon hearing the colours, the poem rolls on gently, cinematically following Munch as he makes more purchases, for what we presume may be a simple brunch. The Greggs sentence works especially well because it spans a stanza break, giving the reader a pause before delivering another almost Magical Realist moment. Does that ‘seems to’ dilute its power? I don’t think it does; it bestows the feeling that not everything is knowable and so, paradoxically, makes the possibility more plausible. I recall the strange incident in the folk-horror film Midsommar (dir. Ari Aster, 2019) where the American protagonist Dani appears to be able to understand and speak Swedish as she dances with young women from the Hälsingland village where most of the film is set.

Then we get the ‘Scream’ incident, relayed with commendable economy – ‘some sort of turn’ – and, once again, a mid-sentence pause across couplets. Perhaps there should be an em-dash rather than a comma after ‘happened’, though the meaning is still clear, and this, the longest sentence in the poem, ends with the comfort and reassurance of that delightful ‘the world stays still again’. A case could be made for saying that the poem should end there, but I’m glad it doesn’t: the final couplet augments the sense of stillness and peace provided in the penultimate couplet. We implicitly picture Munch tossing into the river some of the bread he bought earlier, and using the flask he bought then filled at Greggs. This pulling together of threads is sonically completed by the half-rhyme of ‘ducks’ and ‘flask’ – and which wouldn’t work half so successfully if the poem were in quatrains.

As a whole, the poem seems to be incidentally telling us how the creative process, and the flashes of brilliance involved therein, can derive from the most mundane of activities; above all, from taking a nice constitutional – which is what I’m off to do now.

I must reiterate that this splendid poem sits among 23 other immensely readable and enjoyable poems in Sub/urban Legends. Pam will be launching it with the equally terrific poets John McCullough and Robert Hamberger, on the evening of 5 June in what promises to be a very memorable event. Free tickets can be obtained here.

-

Poem in The Fig Tree – ‘Cul-de-Sac’

With my thanks to editor Tim Fellows, I have a new poem in the latest issue of The Fig Tree, here, alongside some excellent poems by some very fine poets, including Stewart Carswell, David Harmer, Fokkina McDonnell and Mat Riches.

-

April reading

I read about Boot Sale Harvest by Adrian May, Dunlin Press 2023, available here, on the Caught by the River website and had to buy it. Ostensibly, it recounts a year’s worth of May’s hauls from car-boot sales near his home in North Essex, but May’s riffs on a variety of themes – Essex itself, literature (good and bad), religion, all manner of objects (practical and otherwise), the highs and lows of his love life, and, above all, music (he’s been a folkie for many years) – are engagingly idiosyncratic and off-piste. He frequently rambles, but don’t we all. As Ken Worpole says in his foreword, ‘There are in Boot Sale Harvest similar elements of the delight which millions found in the critically acclaimed television series, Detectorists.’ The locales in the book are reminiscent of the fictional Danebury of the series, the characters are equally quirky, and May subtly chews over the mostly male obsession with collecting, in a way which reminded me of an anecdote of Lance’s in Detectorists in which he talks about a bloke who ended up collecting collections. May intersperses the book with some of his song lyrics and poems, the former being rather more palatable and entertaining than the latter. It’s one of those chatty books which makes for amusing, melancholy and thoroughly amiable company.

Talking of Ken Worpole, he is the guest on the latest edition of Justin Hopper’s excellent ‘Uncanny Landscapes’ podcasts, here. At one point Ken starts talking about how annoyed he was when John Major’s government brought in the idea of people as ‘customers’ when they interacted with local government and other public services. Personally, it never bothered me, because ‘customer’ was also followed by ‘care’ where I worked, and I always made sure that my teams went out of their way to provide the best possible customer care. For me, what Major’s government was and remains sadly responsible for is introducing the hideously Tory notion of ‘choice’ in public services, since choice was invariably an illusion (the choice to have no choice, if you like it) for those people who needed the most help, e.g. those living in social housing were often the least likely to have a good choice of schools – if you believed the school league tables which Major brought in – to which their children might gain admission, whereas those with the money to move near or next door to the ‘best’ schools definitely did have choice, and even more so if they could also afford to send their kids to private schools if they wanted to be even more selfish. I spent years trying to make school admissions fairer in the areas in which I worked, but I digress.

I also very much enjoyed, and admired, PJ Kavanagh’s The Perfect Stranger (originally published in 1966 and reissued by September Publishing in 2015, available here), a memoir covering his childhood, adolescence, a spell as a Butlin’s redcoat, a sojourn aged 18 in Paris in 1949, National Service (including being wounded in Korea), studies in Oxford, love of and marriage to Sally Lehmann, daughter of Rosamund, and her tragic death from polio in 1958. It’s beautifully written, with enviable self-reflection, and absolutely full of the joys of being young and at large in the world. I’ve never read much of his poetry or any of his novels and must remedy those omissions. I do, though, have a copy of the fine job he did in editing his 1982 edition of the collected poems of Ivor Gurney.

As far as I know there are three biographies of Philip Larkin: Motion’s, the far superior one by James Booth and the one, entitled First Boredom Then Fear, by Richard Bradford. I hadn’t read the latter until the other week, having bought it at Sheffield’s best secondhand bookshop, Kelham Island Books and Music. It’s much shorter than the other two, but contains much more information on Larkin’s childhood and is far and away the best in how it relates Larkin’s character and life to many of his most well-known poems and to some which remained unpublished.

Rebecca Goss is a poet whose work I have hitherto been unfamiliar. Regular readers may recall that I wrote a brief post, here, commending the podcast Goss recorded last year with Heidi Williamson about poetry of place. Like Adrian May, she lives in the middle of East Anglia, in Suffolk. I suggested her most recent (2023) collection, Latch, published by Carcanet and available here, as the book for next month’s poetry book club. It concerns her return, with her husband and young daughter, to the area she was raised in, after living for a long while in Liverpool, and the memories it sparked. At times, it felt like the rural feel had transported me back to the prose of Ronald Blythe in his unclassifiable classic Akenfield. (Though when I think of Suffolk and writers, Roger Deakin, Michael Hamburger and WG Sebald, all of whom I’ve written about on here, also come to mind, as does George Crabbe.) Three poems from Latch were first published in Bad Lilies in 2021, here. As you can see, Goss writes beautifully about a country upbringing. I’ve also now read – in one sitting – her very moving and transfixing second collection Her Birth, about, principally the birth and death of her first daughter Ella.

I really got stuck into Patrick McGuinness and Stephen Romer’s translations of selected poems by Gilles Ortlieb, published in 2023, in a dual-language edition, as The Day’s Ration, by Arc Publications, available here. With a fine but arguably superfluous introduction by Sean O’Brien, Ortlieb’s poems invariably consist of small observations and his thoughts about them. He is from, and still lives in, an industrial part of Lorraine, in north-east France, next to Luxembourg and, of course, Germany. ‘Sleeper Gravel’ (‘Ballast Courant’) will serve as an example of Ortlieb’s style:

A trail of stones reddened this evening

by the last sun that covers the rarely lit

back wall of a bedroom, glimpsed

on the upper floor of a villa

in Uckange, or a frontier suburb:

fragile goldwork, inlaid already

with the spreading gloom, that interval,

before the coloured gems of TV sets

light the house fronts further on.

Small distracted thoughts, in a swarm,

see us over the gulf of every evening.

Having read a few collections and a novel by McGuinness in the last year, I can very easily see why he likes Ortlieb’s poetry, with its quietly sardonic phrasing, its in-between and otherwise overlooked environments and Existentialist attitude. (I can’t vouch for Romer, having not – yet – read his poetry en masse.) As far as I can tell, with my rusty A-level French, the translations aim to convey Ortlieb’s general rather than literal sense. Often, they take liberties with his lineation, but on others they try their best to match the dense slabs of Ortlieb’s poems. It’s my favourite book of ‘new’ poems this year, albeit that they cover the length of Ortlieb’s fifty-year career.

Now I’m working my way deliberately slowly through Jane Hirshfield’s amazing set of essays, Nine Gates, subtitled ‘Entering the Mind of Poetry’, published by Harper Collins back in 1997. As you’d expect from Hirshfield, it’s immesely thought-provoking; the best book I’ve read about poetry in a long time. It would be very difficult to try and summarise Hirshfield’s ideas. If I were the sort of person who defaces books by using a highlighter pen to mark the best bits, then my copy of Nine Gates would look like an Acid House night had been held within it. This sentence is typical of Hirshfield’s Zen-infused (cliché alert, sorry) insights: ‘Originality lives at the crossroads, at the point where world and self open to each other in transparence in the night rain.’

-

The Last Corinthians – pre-ordering and online launch

Cover of The Last Corinthians My forthcoming poetry collection, The Last Corinthians, is now available for pre-order at the Crooked Spire Press website, here.

Also, tickets are available, here, for the online launch on Tuesday 10 June, at 7pm, when I’ll be joined by two fantastic poets, Shash Trevett and Cliff Yates. I hope you will be able to join us.

-

My forthcoming poetry collection: The Last Corinthians

It’s taken me a long time to assemble my second collection of longer-form poems into a coherent state, eight years since my first. I’m delighted to say that it will be published this June, by a new, Derbyshire-based publisher, Crooked Spire Press.

Crooked Spire Press has been founded by Tim Fellows, the editor of the online journal The Fig Tree. I am immensely grateful to Tim, not least for his patience.

I’m also very grateful to the members of the fortnightly workshop group I’m part of, the Collective, whose comments on drafts of a good number of the poems in the book have been very helpful; and to many other poets and other friends who have given me encouragement over the years.

The Last Corinthians includes poems previously published in The Fig Tree and a variety of other journals, including: 14 Magazine, The Alchemy Spoon, Atrium, Bad Lilies, Black Nore Review, The Friday Poem, The High Window, The Honest Ulsterman, The North, Obsessed with Pipework, One Hand Clapping, Pennine Platform, Poetry Salzburg Review and Wild Court.

There will be several launch events, as below. It would be lovely to see readers of this blog at them. My thanks to the lovely and brilliant poets who will be reading alongside me.Saturday 7 June, 2pm, free

Dystopia Bar (upstairs), Doncaster Brewery Tap, 7 Young Street, Doncaster, DN1 3EL; with Victoria Gatehouse and Ed Reiss. Free. No booking necessary.

Tuesday 10 June, 7pm, free

Online; with Shash Trevett and Cliff Yates. Free. Tickets are available here.

Tuesday 17 June, 7pm for 7.30, free

The Devereux, 20 Devereux Court, Temple, London, WC2R 3JJ; with Vanessa Lampert, Ian Parks and Mat Riches. Free. No booking necessary.

Tuesday 16 September, 7pm

Five Leaves Bookshop, 14a Long Row, Nottingham; with Kathy Pimlott and Peter Sansom. Tickets are available here.

Cover of The Last Corinthians

-

On another haiku by Simon Chard

the day’s gentle start lesser celandines

This is the winning haiku, and therefore featured, haiku for April on this year’s Haiku Calendar, still very much worth buying from Snapshot Press, here.

Longstanding readers of my blog will know that I believe Simon Chard is one of the very best English-language haiku poets writing today. This example of his work is deceptively simple. It’s written as a one-liner, but it consists of two almost equal-length parts:

the day’s gentle start

lesser celandines

But haiku written as two lines look a bit odd, don’t they?

It would also have been too awkward to have forced this haiku into three lines, because of that possessive apostrophe:

the day’s

gentle start

lesser celandines

Therefore, from the angle of appearance alone, Chard has undoubtedly made the right call in presenting this moment as a one-line haiku.

But what exactly is this moment? Well, for one thing, it’s really two moments – which presumably are so consecutive as to be all but conflated: the realisation that the (unseen) poet-persona’s day has got off to a gentle, and presumably good, start by way of, perhaps, a woodland walk, and then the noticing of the flowers.

Or, in fact, it could be that the noticing of the flowers preceded the thought and, moreover, triggered it; that the sight of the flowers has slowed the poet down, made him more fully in tune with time and place for a fraction of this spring morning (assuming that he hasn’t been abed until noon or gone!) and enabled him to ease himself into the day.

Either way, this is a poem brimming with optimism.

As readers, we presume, surely, that it’s a sunny morning, with blue skies, and that the sunshine has caused the celandines to unfurl. Their bright yellowness resembles a child’s conception of the sun their petals spoking like the sun’s rays. Richard Mabey, in Flora Britannica (Chatto and Windus, 1996), says that the word celandine

derives from the Greek chelidon, a swallow.’ The sixteenth-century herbalist Henry Lyte suggested that this was because it ‘beginneth to springe and to flower at the coming of the swallows’. But most celandines are in flower long before the swallows arrive, and it looks as if the lesser celandine may have been confused with the greater celandine, another yellow-flowered but quite unrelated species.

Mabey goes on to venture, quite reasonably, that the name suggests the flower ‘was seen as a kind of vegetable swallow, the flower that, like the bird, signalled the arrival of spring.’

He reminds us too, incidentally, that the flower’s most common alternative English name, historically at least, is pilewort, for its effectiveness against haemorrhoids. Meanwhile, Václav Větvička, in Wildflowers of Field and Woodland (Hamlyn, 1979), states that:

With its numerous tubers, Lesser Celandine is one of those plants which people often used to have to eat in mediaeval days during times of poor harvest or famine. Aptly then, it was called Manna from Heaven. Perhaps it is this historic role which has given rise to the German names Feigwurz, meaning root-fig, and Scharbockskraut (the most common name), a medicine for scurvy (a disease in times of want).

As I’ve written elsewhere, haiku which contain leading statements don’t usually float my boat, because they tell the reader too much. Here, though, the clause ‘the day’s gentle start’ is more like a compound noun – the sort for which German is renowned – than a statement, despite the fact that it does lead the reader in a certain direction. As such, the haiku reads like a succession of nouns which, thanks to the one-line form, elide to become one, in a single, heightened moment of simplicity and gladness. We can easily intuit Chard’s restrained joy. That ease does not make the poem any less effective; on the contrary, it allows the readers to stand in the poet’s shoes or boots and revel in the beauty of a delightful spring morning after the dull days of winter.

-

Review of Hannah Copley’s Lapwing

With thanks, as ever, to Hilary Menos and Andy Brodie, my review of Lapwing (Liverpool University Press, 2024) by Hannah Copley is up at The Friday Poem, here.