My mum passed away in the early hours of Sunday morning. Here she is in, I think, the late ’Fifties.

My mum passed away in the early hours of Sunday morning. Here she is in, I think, the late ’Fifties.

I was sad to hear today of the passing of Les Murray. In September 2015, Hamish Ironside (pictured with Les below) and I went for dinner and a few pints with Les at the Anglers in Teddington when he was over for a reading tour and was staying, curiously, in the same hotel as the All-Blacks who were over for the Rugby World Cup.

We talked of poetry of course, but also of haiku, in which he was very interested, not least because of his friendship with the American minimalist Gary Hotham. Les spoke, too, of his early days in London in the late ’50s and early ’60s, when he hung out with Peter Porter, Germaine Greer, Barry Humphries and Clive James, and also of his more recent friendships with Pascale Petit and other British poets.

The next day at work I kept having to pinch myself that I’d been down the pub with one of the greatest poets of our time.

Of late, my reading seems to have been stuck in an early-Twentieth Century time-warp: Ivor Gurney’s Collected Poems – his post-war war poems are undisputedly great, as well as others concerning his native Gloucestershire, especially during the two years 1920–22 immediately before his confinement in asylums, for the rest of his life; Helen Thomas’s beautiful and desperately sad memoirs of friendship, courtship and marriage to Edward, As it Was and World Without End; Edward’s poetry, a perennial favourite, so full of plein air existentialism before the word had even been coined; and HG Wells’s novels, The History of Mr Polly and Kipps. To an extent, I’ve been led back to such reading-matter by Glyn Maxwell’s incredibly good On Poetry, and his maxim, “You master form, you master time”, and his repeated insistence that line-breaks and stanza-breaks are forms of punctuation as vital as commas, full stops and the rest.

Consequently, my writing has been enriched, I think, by reading more carefully and more slowly; by not galloping through poems but taking more time to look properly at how black type imposes itself upon white space. I find it difficult to write about life today and worry that I’m simply a poet of memoir. Working my socks off in local government at a time of having to do far more with less funding and fewer resources means I get enough of contemporary life for most of my waking hours. Outside work, the impact of political callousness and uncertainty and the hideousness of Brexit inevitably drive me back into memory. But I’m not harking back to any golden age, because it’s obvious to everyone – except to the racists who are increasingly infecting our society again – that one never existed. It begs the question, though, of how one can write about the past without seeming that one is harking back somehow. The answer surely lies in doing so with affection where it is warranted and without any rosy-eyed sentiment when it evidently isn’t.

I’ve also volunteered myself as family archivist: I have boxes of documents, of family tree research undertaken by my paternal grandparents in the Fifties and Sixties, and amazing photo albums going back to late Victorian times. They are a trove of material. Of course, such materials trigger loads of questions which, to my constant sadness, it’s too late to ask.

This time last week, 10 of my fellow Poetry Business Writing School 2017–2019 poets – David Hale, Keith Hutson, Hannah Lowe, Marie Naughton, Stephen Payne, Kathy Pimlott, Emma Simon, David Underdown, Tom Weir and Rod Whitworth – and I were preparing for our end-of-programme celebratory reading in the Jerwood Centre next to Dove Cottage in Grasmere, as the culmination of our residential weekend at Rydal. Unfortunately, our twelfth member Ramona Herdman was unable to take part. in the reading.

Despite all weathers, including snow and hail, we had a sizeable audience, including Wordsworth Trust poet-in-residence and New Networks for Nature steering group member Matt Howard. It was a special occasion and the happiest reading I’ve ever been part of. I can’t speak highly enough of Ann and Peter Sansom, whose guidance, knowledge and wisdom have been a constant source of inspiration for the last two years.

On her website, Kathy Pimlott – whose new Emma Press pamphlet Elastic Glue is a must-read – gives an eloquent account of how and why being a member of the group has been so inspiring. For my part, I couldn’t have wished to have had nicer, more encouraging colleagues. We hope to have some reunion readings in due course.

I’ve enjoyed the programme so much that I’m doing it all over again, in the 2019–2021 cohort, for which I am very grateful and excited!

Lawrence Sail is one of those poets who seems to have been around for years – probably because he has. I wasn’t aware of his poem ‘The Cablecar’ until Ann and Peter Sansom used it as an exemplar in one of their Poetry Business Saturday writing exercises.

It immediately grabbed me as a wonderful poem, by which I mean a poem full of wonders and surprises. The shape and form of it – three chunky stanzas of seven lines each, with irregular syllable-counts per line – proclaims substance and so it proves.

That mellifluous opening pitches the reader straight into a nameless ski resort somewhere in the Alps. How often do poetry tutors enjoin participants to avoid adverbs? Yes, you can over-use them, but sometimes they work brilliantly. Sail’s use of ‘lightly’ in the first line is perfect: positioned mid-line, it’s like a stepping stone between ‘silver’ and ‘valley’. Although the primary meaning is that the cablecar moved with lightness, it might also imply a sense that the ‘silver box’ gleams with sunlight. If one reads the line without ‘lightly’, its absence is marked.

Then that extraordinary metaphor of the second line is sprung: ‘ape-easy’ is daring writing which trusts the reader to follow Sail’s thought. These days, many poets seem either too afraid to use metaphor and instead use simile, or they use metaphors which are so convoluted or absurd that they serve only to baffle or irritate the reader.

In the third line, the reader realises that the narrative persona is within the cablecar and not observing it from afar. There’s a Larkinesque feeling to ‘it had shrunk the town to a diagram’ – reminiscent of that magical line in ‘The Whitsun Weddings’: ‘I thought of London spread out in the sun,/ Its postal districts packed like squares of wheat’ – and indeed to the rest of the first stanza as a whole. There’s a lovely musicality to ‘the leaping river to a sluggish leat of kaolin,/ the fletched forests to points it overrode’. I confess I had to look up the word ‘leat’ – a watercourse leading to a mill – but I’m glad that Sail took the risk of using an uncommon term, the first of three within the poem, as we’ll see. The adjective ‘fletched’ is marvellous – I can see the chevron shapes of the fir trees’ branches, no doubt covered in snow. I don’t quite get ‘to points it overrode’. The last two lines of the stanza introduce a note of scientific curiosity, of the physics which drives the cablecar upwards. They also introduce the addressee – the ‘you’. Who is that? Is it just Sail’s way of trying to put the reader into his shoes?

The second stanza, like the first, opens energetically with a verb and then that perfect use of ‘whisked’. I can’t find the word ‘slurs’ defined as any kind of natural feature but I presume that’s what Sail must mean – like ‘moraine’, the masses of stones left after a glacier. I had to look that word up too, as I couldn’t quite remember it from O-level Geography. And then the poem takes the turn which you somehow expect, of the fear felt when the cablecar stops mid-air. It concentrates its focus on the immediate circumstances, in contrast to the wide lens of the first stanza. The anaphora ‘It had you[r]’ in three successive sentences works brilliantly because it echoes the halting progress of the cablecar. Sail’s use of different senses, his rendering of the various sensations and his alternation between long and short sentences all build vertiginous tension which climaxes with ‘It made you think of falling’. I had to look up ‘seracs’ of course, to find that they are columns or blocks of glacial ice.

Another reason why I like this poem so much is that the three stanzas are all self-contained parts, or movements, of the story that the poem narrates – so the stanza breaks are in the right places and there’s no artificial division into neat stanzas. So the third stanza, like the second did, provides a shift from the stanza which preceded it. The detail is on a wider scale again: ‘the broad-roofed houses decorated with lights’. Most impressively, though, is the very clever way in which Sail, with such sleight of hand, enables the narrative to relate the scene at the top of the cablecar’s route in retrospect, as ‘you’ are ‘lowered back to the spread valley’, because it allows the poem to end with five lines of glorious epiphany. The descriptive phrases Sail uses – ‘the giddy edge/ of snowfields still unprinted, that pure blaze’ and ‘a glimpse/ of the moon’s daytime ghost on solid blue’ – make beautiful, truly poetic lines without seeming forced. Again, I’m reminded of Larkin, specifically his mystical tones in the endings of ‘Here’, ‘The Whitsun Weddings’, ‘An Arundel Tomb’, ‘High Windows’ and ‘The Explosion’.

school bell . . .

her anorak wings

wheel with the rooks

Jane McBeth

This is a March haiku from The Haiku Calendar, and a charming one, I think. It’s full of life and gorgeous observation, and just the right side of being too sentimental.

The sound combinations are instantly attractive – bell/wheel, -rak/rooks and wings/wheel/with – and help to bind the poem together. The Greenland-Inuit-derived word ‘anorak’, when used in its original meaning of an outdoor jacket rather than as a metonym for an obsessive, is happily anachronistic, as it instantly reminds me of the Seventies, when every kid wore an anorak.

It’s as though there’s a gust of wind which is making the back of the girl’s anorak ride up like wings when she hurries back into school at the ringing of the bell, but McBeth has the sense to let the reader intuit the presence of the wind.

The word ‘wheel’ is often used in combination with rooks, as in David Cobb’s haiku published in Blithe Spirit in 1992 and anthologised in Wing Beats in 2008:

after the fall

seeing the rooks wheel round

behind the poplars

I’m not convinced Cobb’s haiku needed ‘seeing’, and I vaguely remember him saying as much. The half-rhyme of fall/wheel does the same job as McBeth’s bell/wheel, but in a more forced way, since Cobb, as an Englishman, would much more naturally use the word ‘autumn’ than ‘fall’, though the latter is, of course, shorthand for the actual leaf-fall. For that reason, and because of its subtle application of ‘wheel’ to the ‘anorak wings’ rather than the rooks, McBeth’s haiku is arguably more interesting.

Throughout February, the following haiku, by John Stevenson, has been periodically catching my eye on my desk at work, as it’s featured on this year’s Haiku Calendar, from Snapshot Press:

canned peaches

the darkest corner

of the cellar

Verbless haiku or senryu, without any action for the reader to imagine, are often rather cerebral and this one certainly is. It relies, it seems, not on the surface scene (presuming, that is, that the two elements actually make up one scene), but on the associations which the nouns have for the reader.

The first line reminds me of having tinned peaches, with evaporated milk, as pudding after Sunday roasts in the ’70s, and also of the Dylan Thomas short story ‘The Peaches’.

The rest of the haiku conjures up a (literally) very dark place indeed: that trope of horror films which has been rendered more forbidding by the revelations 25 years ago about Fred and Rosemary West, and 11 years ago about the Austrian Josef Fritzl and the terrible things he inflicted on his daughter for 24 years, and of other similar cases in the States and elsewhere.

So how does the reader bring the two elements together? I’m not sure I’ve found an answer to that question. It might just be that the inhabitant of the house stores tins in the cellar and has to stumble about in the dark to find what s/he is looking for. Alternatively, it might be a picture of a survivalist stocking up tinned food in case of the bomb dropping or other disasters, but that seems unlikely somehow.

If it isn’t either of those, then what leap does Stevenson want the reader to make between the two elements and what exactly or approximately is he getting at? For me, it’s not enough simply to say that the reader will make of it whatever they want, otherwise the writer may as well write put any two elements in a random manner and see what lands. I don’t for a moment believe that’s what Stevenson has done here, since he’s consistently been one of the very best haiku poets in English for many years, yet neither do I think that he’s given the reader, or me anyway, quite enough to go on. All the same, as I say, I’ve been drawn to it repeatedly and it can’t only be the mention of the peaches and the Proustian memories they trigger which has intrigued me.

Sometimes, perhaps, it’s enough for a haiku, like many a longer poem, to pique one’s interest without even half-explaining itself.

Although I remember skimming through it years ago, and being generally aware of Richard Murphy and his links with Hughes and Plath (I remember a piece by Murphy, in Poetry Ireland Review 30 years ago or so, about his friendship with them), Roethke, and the next generation, of Heaney, Longley and Mahon, Sailing to an Island isn’t a book I knew well until a couple of years ago when I acquired a copy.

Like many intriguing collections, it has a thematic, geographic unity: set in, and about the peoples of, a particular corner of Connemara, in the West of Ireland – both the ‘poor’ Catholic folk living off the fruits of the sea and the (once) ‘rich’ Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy to which Murphy and his family belonged, so it’s at once both general and personal. It’s book-ended by poems which show the sometimes destructive power of the sea and is threaded with the (then) recent, post-Irish Independence history of that locality.

It’s comprised of several beautifully-controlled long, narrative poems, and some much shorter, but (mostly) equally effective ones which use a pleasing variety of forms. For example, Murphy, like Plath, especially excelled at terza rima.

Murphy tells ‘big’, dramatic, fast-paced – but not too fast-paced – stories in these longer poems, using vigorous, sonorous language, including muscular verbs, and isn’t afraid to rope-in technical terms to do with boats and fishing; in fact he seems to revel in using them but without being showy about it.

The real heart of the book lies in ‘The Cleggan Disaster’, which closes the first of three sections of the book. It’s prefigured by the long-ish title-poem, by reference to ‘the boat that belched its crew/ Dead on the shingle in the Cleggan disaster’, and another long-ish nautical poem, ‘The Last Galway Hooker’. It acts as a counterpoint of sorts to ‘Sailing to an Island’, which relates a disaster averted. (Incidentally, it may be just coincidence, but the tragic events which inspired the poem – spoiler alert: there are drownings and lots of them! – took place in 1927, the year of Murphy’s birth.) Murphy’s re-creation of what happened is vivid, almost epic, from the outset: ‘The hulls hissed and rolled on the sea’s black earth/ In the shadow of stacks close to the island.’ Obviously with a title that tells the reader that all will not end well, the beauty lies in the pacing and power of the story-telling, but at no time does the narrative feel like prose. I think that’s partly because Murphy varies the stanza lengths, and the sentence lengths, so as to let the story dictate the form, and partly because he’s evidently very good at the technical craft of writing poetry. Take this stanza, roughly a third of the way through the poem, whose language is simultaneously descriptive of the events but within a high, though not too high, register, totally apposite to the story:

The men began to pray. The stack-funnelled hail

Crackled in volleys, with blasts on the bows

Where Concannon stood to fend with his body

The slash of seas. Then sickness surged,

And against their will they were gripped with terror.

He told them to bail. When they lost the bailer

They bailed with their boots. Then they cast overboard

Their costly nets and a thousand mackerel.

It’s a gripping, electric, tour de force of a poem. And to the brilliance of the story-telling, Murphy adds a five-stanza shorter-lined epilogue, set ‘years later’, which acts as a coda to the poem’s symphony. It’s good enough to stand as a lovely poem in its own right, and indeed Plath chose it as the winner of a competition she judged in 1962.

Another poem which stands out is ‘The Woman of the House’, a brilliant, affectionate ‘portrait’, in 26 finely turned quatrains, of Murphy’s grandmother; reminiscent of the poems in Robert Lowell’s Life Studies in which isolated individuals eke out lives which, despite formerly grand family backgrounds, have long ago become pitiable, futile existences. There is rich detail in the poem, especially concerning the features of the house which are stuck in a time long past (‘Hers were the fruits of a family tree:/ A china clock, the Church’s calendar/ Gardeners polite, governesses plenty,/ And incomes waiting to be married for.’) and regarding his grandmother’s decline into dementia, somehow mirroring the decline of the Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy itself.

I’d also highlight ‘Epitaph on a Fir-tree’, which is not so much an epitaph on the tree, but on the long-gone days of the Ascendancy and all its wealth, society weddings, etc. It works as a companion piece to both the poems which precede it (‘The Woman of the House’ and ‘Auction’). The conceit of the tree as a witness to all that has gone on and changed is a clever one.

The poems stand in contrast to the image I have of Murphy, from a friend-of-a-friend who knew him, that the shock of seeing him wearing a purple velvet suit was exacerbated by his considerable height.

Richard Murphy, Sailing to an Island, Faber, 1963.

In his paean to Claire Everett’s ‘editors’ choice’ haiku in the September 2018 issue of The Heron’s Nest, esteemed American haiku poet John Stevenson makes special reference to Claire’s use of the word ‘skedaddles’ and states that he’s not seen it in a haiku before. It certainly can’t be common, and I can’t definitively claim to be the first person to have used it in a haiku, but my haiku below was published, somewhat incongruously, in the Haiku Society of America 2009 members’ anthology, A Travel-Worn Satchel, and subsequently collected in The Lammas Lands, 2015:

white skies

a hare skedaddles

over Wealden clay

It’s a haiku for which I retain a certain fondness, as much as anything for the memory of the place where it was written, somewhere near Sevenoaks, in deepest Kent, on a rather odd work residential course.

By contrast though, what, for me, makes Claire’s use of ‘skedaddles’ so compelling, and much more effective than mine, isn’t its use per se, but the fact that she uses it transitively, in the sense of ‘chivvies’. I’ve only ever heard it used intransitively, so Claires’s usage is refreshing and, to my eyes and ears, innovative – but I daresay it could just be evidence of the North/South divide.

John interprets the meaning of the word as ‘scatters’, but I see it more in the opposite way, of the sheepdog doing its utmost to round up the lambs. Either way, the word, and its intrinsic onomatopoeia, conjures a dynamic which flows seamlessly and mellifluously from the vigorous fresh-air movement of the opening line. It’s a terrific haiku and I’m glad that John and his fellow editors recognised its beauty.

My Sunday running route for the last few months has changed to one that loops round to Sandown Park and Esher, then up to Hinchley Wood, Long Ditton and back to Thames Ditton. The pleasure of the route lies principally in the fact that it takes in three hills, two of them long enough to provide a healthy dose of challenge to my legs.

The downside, though, is the ostentatious wealth on display around Esher. Strange it is that, so often, the more money people possess, the more they withdraw to the fringes of general society, admiring their gravel drive, their security gates, their apartness, away from the gaze of the hoi polloi. Perhaps that’s why George Harrison, on the retreat from fame, bought a house, ‘Kinfauns’, in Esher, in 1964, and why the Fab Four spent far more time there than at any of the others’ houses, including the first demos of many of the songs that ended up on the White Album.

A few weeks ago, I read perhaps the best book on running I’ve ever read, though that’s not saying much: Footnotes by a University of Kent lecturer in English, Vybarr Cregan-Reid. It’s a tad heavy on the science of running, but it’s a literary and refreshingly personal book in many ways – roping in Hardy, Coleridge, Merleay-Ponty and plenty besides – and inches near to the heart of why running is, or ought to be, part of regular life for those who can manage it. In that respect, it leaves, for example Haruki Murakami’s woefully disappointing What I Talk About When I Talk About Running trailing far behind.

But it’s still not the lyrical, poetic book about running which I yearn to read. Maybe, though, the energy, the exhilaration, the mind–body separation, the sheer existential wonder of running can’t be pinned down in words. I’m hoping that the Poetry Business anthology of poems about running, to be published later this year, will go some way to challenging that supposition. One of the co-editors, Ben Wilkinson, has written some good poems on running (as well as several about football), which feature in his collection Way More Than Luck, including one, ‘Where I Run From’, which takes the title of Murakami’s book as its opening line. It’s an under-explored theme in poetry for sure.

So many of my poems are concerned with the past that I sometimes wonder whether I will ever be able to write well about the present, about contemporary life. But then I say to myself that the past refracts upon the present, and the future, so I needn’t fret.

I do fixate on how the passage of time impacts, on today, on how say the amount of time since I started secondary school, in 1978, is now considerably longer than the period from then back to the end of the Second World War; and how some customs and values, in England/Britain in particular, have changed considerably whilst others have stayed relatively constant despite huge technological advances which would have been virtually unimaginable in the late ’70s, even on Tomorrow’s World. I realise I’m hardly alone in my obsession but when it materialises as narrative poetry it does, perhaps, mark me out as out of step with much contemporary poetry. I don’t worry about that unduly though, as fashions come and go, and I like to think that there will always be some readers who like poetry which principally deals with familial and local history in the Twentieth Century and who can read it at face value and/or refract its matter onto their own experience and times.

The temptation in writing about events which happened some time ago – even a long time ago, maybe even centuries before I was born – is to use the present tense to make the narrative more immediate, more exciting, more now. After all, the present tense in contemporary poetry, or poetry in English at least, does seem, well, omnipresent. Ten years ago or so, I went through a period, when I felt that the present tense was de rigueur, perhaps because of years of writing haiku. I believed that the present tense helps the reader, as it bridges the time gap and thereby makes the particular events and circumstances more tangible.

Take, for example, my sonnet ‘Sofas’, which is partly about the Guildford bombings of 1974: whatever impact the poem might have would, I’m sure, have been diminished if I’d written the sestet or the whole poem in the past tense, because, as is hopefully obvious, I’d intended the power of the poem to be sparked by the difference between the present-day scene in the octave and the historical scene in the sestet.

The other poem of mine in the same issue of The High Window, ‘Good Morning, Mr Gauguin’, written – during one of Pascale Petit’s ‘poetry from art’ courses, at Tate Modern’s magnificent Gauguin exhibition of 2010–2011 – in response to the 1889 painting ‘Bonjour, Monsieur Gauguin’, itself an allusion to Gustave Courbet’s 1854 painting, ‘Bonjour Monsieur Courbet’, could have been rendered in the past tense, but the use of the imperative seemed somehow in keeping with both the style of the painting and Gauguin’s character (inasmuch as we can know him from his works and correspondence and from biographical matter about him). Typically, since the poem has been published I’ve revised it into what, I like to believe, is a better poem, but revision of poems is another matter entirely.

Lately, though, I’ve started to wonder whether sticking rigidly to the present tense does historical poems a disservice, as if one is implicitly saying that their contents couldn’t be of any direct relevance to today if they were written in the past tense. In some ways, the historical distance is as valuable and exciting as the relevance for our daily existence today. For me, it’s an interesting problem to grapple with.

Below are the last reviews I wrote in my stint as Reviews Editor (and Co-Editor) for Presence.

Stuart Quine, Sour Pickle

Alba Publishing, PO Box 266, Uxbridge, UB9 5NX, UK;

£12/€14/$16; ISBN 9781910185957; http://www.albapublishing.com

Hamish Ironside, Three Blue Beans in a Blue Bladder

Iron Press, 5 Marden Terrace, Cullercoats, North Shields, NE30 4PD, UK; £6; ISBN 9780995457935; http://www.ironpress.co.uk

I have to declare my interests in reviewing these books – both authors are friends of mine, Quine is also a former Presence colleague, and I was one of three people who read and commented on Ironside’s draft manuscript; but nonetheless these are very good, unmissable books.

Quine is widely recognised as a pioneer and master of the one-line haiku. He has been writing haiku and having them published, mainly in Presence, for well over 20 years, so it may come as a surprise to those who’ve long admired his work that Sour Pickle is his first collection, which is a considerable contrast to the increasingly prevalent tendency of neophyte haiku poets to rush to getting a collection out, often with no filter or sense of how a collection should be edited and cohere. Dedicated to Martin Lucas, the book is divided into the four seasons, starting with spring.

The one-liner as a form gives the haiku poet opportunities which the three-line form doesn’t; it can be used to create ambiguity, by not making explicit where the cuts/breaks should be, thereby lending the haiku multiple interpretations. Quine’s one-liners tend not to do that, however, and it is usually obvious where the reader should mentally insert the breaks, to the point where the reader may wonder why he doesn’t just write them as three-liners, e.g. ‘sushi carousel the blush on the salmon coming round again’ or ‘millstone weir a downy feather slips downstream’. But as with both of these, a case could be made that the form can add another, ‘concrete’ dimension: in the first, the form could be seen as representative of the horizontal nature of the carousel, and in the second it allows the words to gush forth in imitation of the weir.

The form also enables haiku which would look unbalanced if they were set out as three-liners and would really be divided into two parts instead of three, e.g. Quine’s ‘defiant in thin rain the toad on the garden path’ or ‘waiting at the departure gate a discussion of the bardos’, which by any standard are excellent haiku and senryu respectively.

As I’ve noted previously in Presence, Quine has a gift for writing haiku with an air of wabi sabi, such as his echo of William Carlos Williams’s trailblazing Imagist classic ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’: ‘everything depends on this old bucket left out in the rain’. One could argue here, though, that the form doesn’t bring out the best of the haiku; as in Williams’s poem, the words need to unfold more slowly than the one-liner permits, and inserting breaks after ‘depends’ and ‘bucket’ would have naturally allowed that to happen.

I especially like this wabi sabi example too: ‘gone to seed in the coupling yard grey beards of willowherb’. It exemplifies Quine’s talent at spotting and celebrating the small things in life, and rendering them into poems which may use simple language but still sound wonderful on the ear. Furthermore, the reader could additionally interpret the image as a kind of self-portrait by its writer.

Quine also uses the form to write haiku which have a beautiful, musical sense of movement, to the point of being tongue-twisters:

the windbell’s streamer wildly spinning March winds

along the strandline seaspray and sunshimmer in knotted kelp

In the first of these, ‘March winds’ look as those they are wrongly positioned, i.e. that they should come at the beginning, but Quine’s ordering facilitates a reading worthy of Existential philosophy, that it is only by their impact on physical objects that one becomes aware of the winds. In the second, Quine sets before us an array of natural phenomena concentrated within the visual alliteration of ‘knotted kelp’.

Presence readers have regularly voted Quine’s quietly observational and sometimes more personal, and even self-deprecating, haiku at the top of their ‘best-of-issue’ choices and I won’t set them out here, but readers of this essential collection will come across many old favourites and classics. The prevailing mood of Quine’s haiku is predominantly downbeat and autumnal whatever the season, and occasionally to the point of despair; but that is no bad thing, because what they do so well is set out eternal truths in a clear and frankly marvellous way that so few English-language haiku poets can match:

deep in the hills the ruffled moon silvers the tarn

*

Ironside’s collection is a sequel of sorts to his first collection, Our Sweet Little Time, and, like that book, sets out the best of a calendar year’s worth of haiku, with each month featuring a delightful black-and-white linocut by the artist Mungo McCosh. At only £6, this A6 150-page collection is an attractively designed bargain.

The atmosphere of Ironside’s poems provides a sharp contrast to Quine’s, being more outward-facing and largely concerned with the often comical ups and downs of marriage, family and the general absurdities of middle-aged existence in 21st Century London suburbia. If writing resonant haiku is a difficult art, a case could be made that writing resonant senryu is harder still. Many senryu have an immediate ‘punchline effect and nothing more, especially those which tread well-worn themes such as jealousy of, or schadenfreude at the misfortune of, a neighbour. Explaining how senryu work may well be as pointless an exercise as explaining how jokes work – not that all senryu are comic, of course. It’s a generalisation, but, on average, I contend that senryu tend to be more immediate in ‘meaning’, and less slow-burningly resonant than, haiku. It therefore takes considerable skill to write senryu which defy that tendency by succeeding in having both an instantly graspable ‘a-ha’ appeal and a deeper layer of meaning or suggestion. I would suggest that, among British haiku poets, only the two Davids, Cobb and Jacobs, can compete with Ironside when it comes to writing wry, resonant senryu:

for good measure anti-war march—

the cash machine delivers we join it for a few steps

an electric shock to get to the shop

Ironside is particularly good at wittily capturing the loving rivalry between family members, between he and his wife and as the butt of his daughter’s incisive observations, but usually (as with all the best humour) with a hint of an underlying seriousness, e.g. ‘mental health ward— /my wife asks how they’ll know / I’m not a patient’ or ‘sunlit rain— / my daughter figures / how long I’ve got left’. Ironside manages to balance the comedy with the darker side of life in a manner which is perceptive and finely nuanced.

Several of the poems feature Ironside’s day-job as a freelance editor, typesetter and proof-reader, e.g. ‘working weekend— / the Oxford Spelling Dictionary / shouts asshole at me’. Indeed, Ironside’s ability to laugh at himself and point out his own weaknesses is a characteristic he shares with Quine. There the comparison ends, though, because Ironside’s use of language and subject-matter is much more varied, sometimes to the point of nearing the boundaries of the homogenous consensus of what a haiku looks like: ‘the myth of pleasure . . . / Saturday night vomit / in Sunday morning rain’ and ‘a spider snares a wasp / with the overelaboration / of a Bond villain). I’m not sure that the first line of the first of these adds anything to what the reader could have deduced from the rest of the haiku; it almost acts as a metacommentary or maybe as a Hogarthian warning. But no-one could deny that it’s a haiku of sorts. In the second, I like the fact that the poem itself is elaborate, and I don’t think it really matters if it’s a haiku or not because it succeeds as an amusing, if dark, observation. There are several other examples which are more extreme (or ‘experimental’ as the back-cover blurb puts it), but they are almost always intelligible, and they make up a small minority within the overall context of Ironside’s rich and varied collection.

Ironside can also write traditional haiku on classical themes, e.g. the simple but lovely ‘autumn— / an old woman / twirling her pigtails’; overall, though, his trademark reflective humour shines brightest, as in this, which features that trope I mentioned earlier:

our nervous cat

seems so relaxed

in the neighbour’s garden

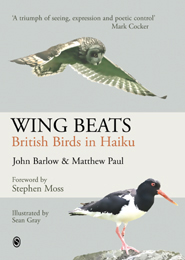

It seems incredible to me that Wing Beats, the book of haiku about British birds which I co-wrote and edited with John Barlow is now 10 years old. It began as a dual collection between the pair of us, but we opened it up to submissions, so that we could include haiku by most of the best haiku poets in Britain who were writing at the time – such as Pamela Brown, David Cobb, Keith Coleman, Caroline Gourlay, Martin Lucas, George Marsh, Matt Morden, David Platt, Stuart Quine, Helen Robinson, Fred Schofield, Ian Storr and Alison Williams – and the book was unquestionably much richer and more varied because of their contributions.

We were fortunate enough to have the encouragement and endorsement of the writer, broadcaster and TV producer Stephen Moss, who wrote the introduction and then generously included the book among his nature books of the year in The Guardian, and of the great nature writer and Country Diarist Mark Cocker.

On re-reading the book, I reckon that some of the haiku, especially some of my mine, wouldn’t pass cut the mustard were we editing it today, but I’m proud of it still, not least because of its lasting influence on English-language haiku as a counterweight to much of the cryptic, frankly unintelligible stuff which is peddled as ‘good’ haiku in some haiku journals and on social media, particularly Twitter.

John put a huge amount of effort into the book, in terms of both content and design: his 127 poems; the six remarkable, scholarly appendices which constitute the end-matter; the integration of Sean Gray’s beautiful illustrations; and the faultless layout and attention to detail. John is a genius whose devotion to haiku is acknowledged well beyond these shores. It was a true labour of love.

We co-wrote the introduction, but this sentence from it has the Barlovian imprimatur firmly upon it, “All the haiku in Wing Beats concern ‘real life’ experiences, ensuring the book has genuine value as a record of wild birds in Great Britain at the beginning of the twenty-first century”. I can’t argue with that.

Wing Beats is still available on the Snapshot Press website, here.

I’m delighted to have a poem in this new anthology, edited by Matt Barnard and published by The Onslaught Press, which marks 70 years since the foundation of the National Health Service by Attlee’s government. My poem, ‘On Muybridge Ward’, is a companion piece to the poems about my dad in The Evening Entertainment, so it has an emotional importance for me.

The anthology celebrates the fantastic efforts of the NHS workforce, despite the Government’s privatisation agenda, by people like my wife, Lyn, who’s worked as an NHS nurse since the ’90s. My mother’s father, Gil Bird, was a nurse at St Thomas’s for 33 years, the last 13 after the inception of the NHS.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t make the book’s launch at Aldeburgh last night, but I hope to read at the London launch in the New Year.

Proceeds from the anthology go to the NHS Charities Together and it contains some wonderful poems by stellar poets, so it would make a perfect Christmas present.

Aquarium with Toddler

Lit-up rectangles filled with the weird:

a baggy-headed octopus with a salad of legs;

lobsters, big-clawed, like futuristic war machines;

pinstripe and leopard print shoals.

In the giant tank the flat-bellied sharks

fly over us, swallowing the bloodless water.

Glum piranhas congregate by the bubble filter.

A ray hangs like a shirt on the line.

What happened to the infinite expanse?

Where is the push of the tide? Jellyfish

bulge and flutter like see-through hearts,

crabs fold up against the perspex.

Safe in his pushchair, Thomas sees the blue TVs,

hears the bathroom sounds, a mish-mash

wattage of fish floating past him, dancing

for his fingers, shrunk by his tapping.

David Borrott

If I were to think of a poem featuring an aquarium, it would be Robert Lowell’s seminal ‘For the Union Dead’, which uses the faded grandeur of the South Boston Aquarium as one of several metaphors for the decline of the values for which the Union stood in the American Civil War:

The old South Boston Aquarium stands

in a Sahara of snow now. Its broken windows are boarded.

The bronze weathervane cod has lost half its scales.

The airy tanks are dry.

Once my nose crawled like a snail on the glass;

my hand tingled

to burst the bubbles

drifting from the noses of the cowed, compliant fish.

My hand draws back. I often sigh still

for the dark downward and vegetating kingdom

of the fish and reptile.

But until I read David Borrott’s 2015 pamphlet Porthole, published by Smith Doorstop, I can’t remember having encountered a poem which had its primary concern the sad reality of a public aquarium. As you can see, though, Borrott’s poem ‘Aquarium with Toddler’ addresses that reality head-on and then some.

Because I took my children around a good few aquaria over the years, including the depressingly awful one in County Hall in London, I was instantly grabbed by the poem’s title. Happily, the content more than lived up to the title’s promise. For me, it’s a poem which is consistently excellent from start to finish.

The opening places the reader right into the aquarium, where the brightness of the illuminated “rectangles”, echoed later in the poem by their description as “blue TVs”, stands out against the implicit claustrophobic darkness; and where “the weird” is the stock-in-trade of the aquarium as the way to entice the punters. The darkly comical evocation of an octopus as “baggy-headed” and “with a salad of legs” somehow manages to be both precise and vague – we sort of know what Borrott means and we can’t help but admire the superb and, to start with, very funny observation of “a salad of legs”. The simile of the lobsters as “futuristic war machines” is perhaps less convincing, but nevertheless this is confident, adventurous writing. The fourth line accurately and economically portrays the patterns of the fish.

In the second stanza, the desultory existence of the creatures is laid bare, in a fashion reminiscent of Lowell’s ground-breaking poems in Life Studies. Borrott doesn’t tell us that the “giant tanks” are featureless and devoid of stimulus for the sharks and piranhas, and that no predation is permissible, but we know they are; his straightforward yet subtle descriptions do as much work through what they tell us indirectly as they do explicitly. As the cliché goes, sometimes less is more. The anthropomorphic use of “glum” works well, not just on its own terms but as a mirror image of the visitors, because the reader intuits that their reaction to what visitors see at the aquarium quickly passes from an initial wow factor of seeing mythically dangerous creatures up close and personal to one of pity and sadness at seeing them boxed up lifelessly for humans’ benefit rather than theirs. The depiction of the ray is particularly acute and fine, and again calls Lowell to mind, specifically the ending of his great poem ‘Memories of West Street and Lepke’ where the incarcerated and lobotomised gangster Czar Lepke, on Death Row, was “hanging like an oasis/ in his air of lost connections . . .” One gets the sense from Borrott that there is more life emanating from “the bubble filter” than from the sharks and fish.

The third stanza makes the point of the poem crystal clear, but in a manner which doesn’t feel like hectoring. Its questions hang for the readers to supply the obvious and more wide-reaching answers. The poet–persona’s discomfiture at being complicit in this imprisonment of our fellow inhabitants of Earth is a feeling that all of us who have ever visited an aquarium, zoo or wildlife park must have experienced. We ask ourselves whether the preservation of animals in captivity is a necessary evil in the fight against habitat loss and extinction, but we find no easy answer. The second of the questions implies that a visit to the seaside to see crabs and jellyfish in their natural surroundings would, after all more worthwhile than this unnatural attraction – but there we wouldn’t see the more exotic, non-European star species of the aquarium’s collection.

That dilemma is naturally linked to education: the more that respect for wild creatures is instilled in youngsters from an early age, the more one would hope that they will grow up to act responsibly towards them. But the last stanza of the poem seems to suggest that the aquarium provides little more than sensory overload for the toddler. Here, Borrott’s descriptive powers are, again, tremendous, with the words sounding beautifully on the ear as well as the page. The perception of the “bathroom sounds” – presumably the artificial gurgling soundtrack which aquaria often see fit to provide in order to enhance the visitor experience – is very well made; and the next clause, “a mish-mash/ wattage of fish floating past him”, is gorgeously onomatopoeic and leads, inexorably, to the child’s-eye view, of the fish being beyond the toddler’s grasp and understanding. The final image of the child doing what the unmentioned warning signs forbid encapsulates all that has gone before it: the fish are “shrunk” by Thomas’s tapping, but of course he’s not old enough to know better. The secondary, implicit meaning is that Humankind in general is demeaned by how it knowingly and immorally treats other creatures. What is surely also implicit is the (presumed) father–son relationship: that the father hopes his child will grow up to become a caring citizen. Borrott tells us that Thomas is “Safe” in the pushchair, but safe from what? Maybe it’s from the awareness that whilst the creatures on display are beautiful, seeing them reduced by their unnatural surroundings instinctively feels morally wrong.

It’s much to Borrott’s credit that he doesn’t preach, and chooses instead to show how things are, leaving us to address and pass judgement on the uncomfortable truth he exposes. His control of his material is perfect, with no wasted words and in a form whose formality suits the importance of the content. It’s a classic, which deserves to be widely anthologised and known.

Porthole, in general, is a delight, with a rich variety of subject-matter, themes and forms. I very much hope that a full collection by David Borrott will be published soon.

David Borrott, Porthole, Smith Doorstop, 2015, ISBN 978-1-910367-43-8, £7.50.

(‘Aquarium with Toddler’ quoted with kind permission of David Borrott.)

It’s been quite a week for me, poetry-wise. First of all, the last Sheffield Saturday session of the Poetry Business Writing Programme that I’ve been on since April last year, then a week’s residential at Sneaton Castle, Whitby, also under the auspices of the Poetry Business.

The Saturday session was our first since the spring, during which time two of my fellow participants had had new collections published, the two, in fact, with whom I’d been ‘paired’ for workshopping and generally corresponding by email with in the intervening period: Marie Naughton and Tom Weir. Marie’s collection, A Life, Elsewhere, is full of delightful gems. I went to the launch of Tom’s excellent collection, Ruin, at Keats House two weeks ago and very much enjoyed hearing Tom read, particularly two football-related poems.

The session flew by with the traditional morning of Ann and Peter Sansom’s ever stimulating exercises followed by workshopping in the afternoon. It seems incredible that – bar a residential in the Lake District, including a reading at Dove Cottage, next March – the programme is finished. For me, it’s not only gained me the friendship of poets whom I admire, but has, I think, greatly helped to sharpen my poetic edges. I can’t thank Ann and Peter enough for having selected me to take part.

The residential at Sneaton from Sunday to Friday was tremendous fun and productive: I wrote more new poems there than I’d managed during the whole of the summer. I recognised most of the participants from Poetry Business writing days and it was lovely to get to know them better. I’m very glad, too, that I came away with some of their publications, which I’ve already tucked into.

On Monday, I’ll be at the Troubadour as one of the poets who’ve been asked to read a favourite poem by a contemporary American poet. I did this earlier in the year, when I did a Stars in Their Eyes turn as Matthew Dickman. Tomorrow, Matthew, I’ll be – well that would be telling.

On Thursday, I’m the featured poet at the monthly Write Out Loud event at the Lightbox, Woking. I can’t wait.

Since it had a longer gestation than a herd of elephants, I shouldn’t have been surprised that it would take a while for my collection to be reviewed, but the wait was more than worthwhile. Thanks to Greg Freeman for his kind and considered review for Write Out Loud.

When I run, my looping route is nearly always clockwise. Now I’ve moved to Thames Ditton, my latest loop is more like a long thin rectangle, a grandfather clock: along the towpath from Hampton Court to Walton, over Walton Bridge and back to Hampton Court via Sunbury and Hampton.

This morning, in the endless heatwave swelter, my legs set off heavily but soon settled into their regular six-minute-mile pace. If I’m running well, the pace is metronomic, to the point of possessing an innate calm intensity, some kind of Gnosticism even. The feeling is simultaneously one of being earthed and unearthly. Sometimes, my mind is telling me that I really don’t want to run fast, but then my legs gallop away from me like an unleashed puppy; other times, I suddenly notice that my legs are running with a fluency that is requiring no apparent effort and no instruction from my brain, as if I’ve switched on the autopilot and completely divorced my body from my mind. Dualism in action.

We’ve had just one interlude in the drought in the last two–three months and that came as a downpour last Sunday, when I was out running. I was so drenched that I had to wipe my glasses on my top every couple of hundred metres or so. The contrast to today, when the heat on my head was searing despite me wearing a cap, couldn’t have been much greater. Water was never far from my thoughts. One of the roads was aptly named Loudwater Close. My routes last week and this took me between, alongside and around some of the great reservoirs and ‘water treatment centres’ of London. For aficionados of Victorian waterworks architecture, and for those who want to convert them for alternative usages, nirvana lies in these parts. By the time I got round to Hampton, I was getting so thirsty that all the Thames Water signs were taunting me, but I dug in. Mind over matter and all that.

It was just about that point that I was reminded of one of my haiku in Off the Beaten Track, which nods, perhaps, to the greatest of Kingstonians, Eadweard Muybridge:

surging wind . . .

the percentage of my run

when I’m off the ground

Last week, I was on an Arvon course at Lumb Bank – a ‘retreat with walking’, tutored, or, more accurately, led, by local mapmaker extraordinaire Chris Goddard and novelist–poet Paul Kingsnorth. Being in Ted Hughes Country in a heatwave meant that I had the time and opportunity to take huge delight in the landscape. Chris knew its paths, even through the woods, and its history so well that he was a brilliant guide. Chris’s books are like Wainwright’s, but with more detail and less trenchant opinions.

One day, Chris met us up at Widdop Reservoir, the subject of one of Hughes’s loveliest poems, ‘Widdop’, from one of his best collections, Remains of Elmet (1979).

It was so hot that most of us got into the water. My poem below attempts to sum up the joy of the moment.

BATHERS AT WIDDOP RESERVOIR

At the shoreline, sapphire bleeds into brown and rust.

It’s thirty degrees and there’s a heap of us

removing walking boots and socks

to take a dip in Hughes’s ‘frightened lake’,

despite the DANGER sign warning against it.

But we do have to mind our step:

treading water is like marching on soap.

Four legs are better: unleashed best-friend mongrels –

Dexy and Alfie – splash my socks

with clay-like mud. One of us dangles

legs from rocks.

Another ventures further out, red-hatted,

immersed to her waist.

Re-socked and booted,

we’re accompanied back to the cars

by a flute band of sandpipers

who scoot along drystone walls from post to post.

Every sun-fed one of us is as properly gripped

as bright adolescents on a Geography field-trip.

In a recent piece in New Socialist, Joe Kennedy analyses the regrettably spurious claim that several British, or more specifically English, works of the last couple of years are ‘Brexit novels’. It’s an interesting read, no more so than when he touches upon Paul Kingsnorth, labelled by the Telegraph as ‘the Bard of Brexit’, and his extraordinary, crowd-funded tour de force The Wake (2014). Kingsnorth’s novel is set between 1066 and 1068, in an England, specifically the Fens, which is coming to terms – or not – with the huge change being wrought by the Norman invaders, and is written in Kingsnorth’s version of Old English made intelligible, with the help of an extensive glossary, for modern eyes and ears.

It’s a tale told by a proud, deeply flawed character called Buccmaster of Holland, a man of some, but limited, standing who vows vengeance on the “frenc” after both his sons are killed at the Battle of Hastings and his “wifman” and then most of his fellow villagers are slaughtered by the waste-laying forces of the Conqueror. He attempts to rouse and lead a band of “grene men” in a guerrilla war, just like the unseen and quasi-mythical figure of Hereward the Wake, a proto-Robin Hood, of whom Buccmaster is irrationally suspicious and jealous.

In fact, Buccmaster is suspicious of everyone, except his dead grandfather whom he reveres for having clung on to the old gods and the old ways; sees treachery everywhere and is, in essence, a fairly unpleasant, yet at times likeable, anti-hero. His opinion of all authority except his own is lower than low, in which regard you could say that he’s like a Brexit-supporting, immigrant-hating, anti-government ‘gammon’, a point which Kennedy expounds upon: “[W]hat The Wake is suggesting is that any ‘rational’ interference, whether in the form of the Norman Yoke or EU sugar beet quotas, of a relationship between person and place that is felt to be intrinsic is an interruption of a natural desire to be embedded.” There is certainly a case to be made that the analogy is a fair one, especially when Buccmaster’s hatred almost turns into nihilism (a theme developed more fully in Kingsnorth’s second, less successful and strangely over-praised novel, Beast), but it’s a rather reductionist one; The Wake is a more complex and haunting novel than that, even though Kingsnorth has, unfortunately, outed himself as a Brexiteer, albeit for anti-capitalist reasons rather than the stereotypical ones.

For me, the most interesting aspect of the book, aside from Kingsnorth’s hugely impressive use of language, is the narrative voice of Buccmaster. Kennedy, rightly I think, sees David Peace as an influence on Kingsnorth, and the other purveyors of this supposed sub-genre. The insistent rantings of Buccmaster, characterised by invective which veers into self-parody, is surely influenced by the similarly bitter and sweary voice of Brian Clough in Peace’s The Damned Utd (2006). Both characters are isolated, stuck in a past which never really existed, and striving for ideals which others are unable to share with anywhere near the same degree of fervour.